From the editor: “L.A. Urbanized” is a series of articles exploring why Los Angeles is currently in the midst of an urban revolution and what it means for the city’s future. It documents the evolving development landscape of the region over the past few decades, identifies what key events brought about its urbanist turn, and considers what the impact of this transformation will be. Urbanize LA will publish one chapter of the 9-part series each Monday from April 2 through May 28.

Market forces do not operate in a vacuum; they interact within constraints set in large part by politics. As we see in last week’s installment, governmental policies regarding growth patterns over the past few decades have constrained development in many of the markets where housing was most desirable, leading developers to seek out new neighborhoods for development (such as Downtown) where opposition forces were less active, but where they might not make as much money as they would had they been able to build in previously established neighborhoods. But there have been other political forces at play in Los Angeles that have shaped development patterns in a much more active fashion. Downtown Los Angeles was the clear center of the region through the 1920s, but in the post-war era its history has been defined mostly by decay and failed attempts at revival. Yet each of these failed attempts, unsuccessful on its own individual accord to ‘bring back’ Downtown LA, did contribute by setting the stage for a Downtown LA that could effectively serve as the preponderant economic and cultural center of a massive urban region, a role its quaint LA 1.0 iteration would have struggled to perform.

“The Blueblood Renaissance”

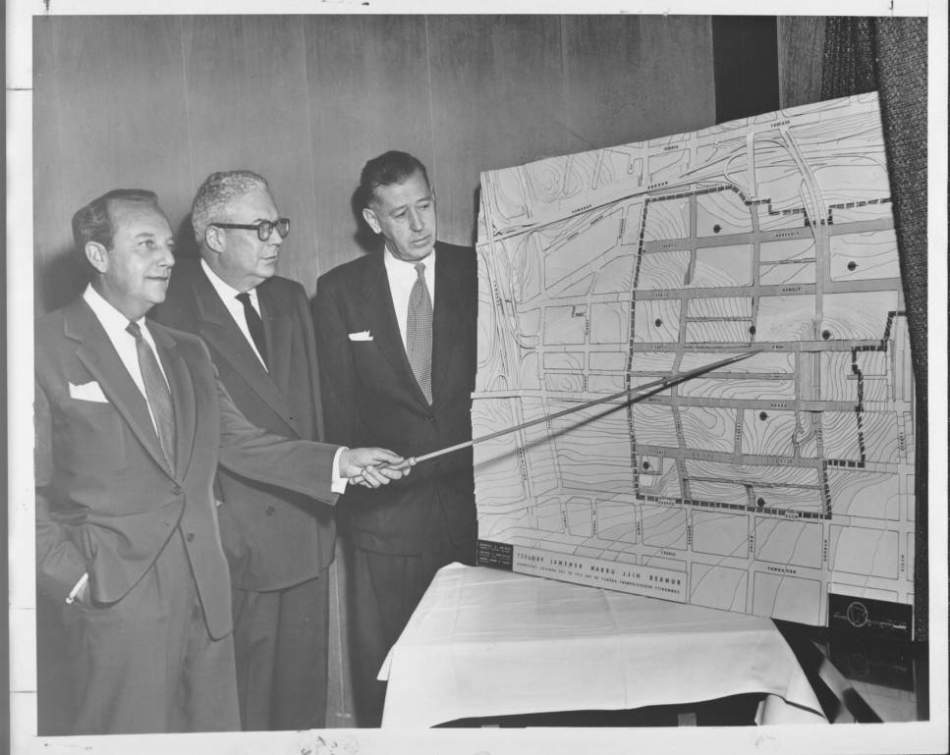

Amongst the more powerful forces in support of these revival efforts were LA’s old ‘blueblood elite’, “the law firms, the banks, the old corporations, the Jonathan Club, the Chandler family of Los Angeles Times fame, and many others who trace their roots back to the engineers of the Los Angeles growth machine.” For this group, as urban planner William Fulton puts it, Downtown in the late twentieth century

“still remain[ed] the center of civic life. It [was] the place where the old power brokers [had] their offices and [did] their deals. It [was] the place where money from across the region [was funneled] in so that it may be transferred and re-invested in new ventures. And, perhaps most important for the bluebloods’ image of themselves, it [was] the place where the allegedly vibrant cultural life of a world-class city [was] supposed to be headquartered.”

For this set of stakeholders, a vibrant and cultural Downtown had greater-than-economic significance. This group viewed itself as stewards of the city, and their vision of its place in the world required such an urban center.

Through the 1960s, the most visible effort of this sort was the creation of the Music Center in the heart of Downtown. This ‘blue blood elite’ considered grand music halls to be a requisite of any great city of culture around the world, and sought to project an image of Los Angeles as “a city of culture and taste and refinement as well as a city of wealth and growth.” So this project became a major rallying cause, championed by Dorothy Chandler, a “society woman” and part of the Los Angeles Times’ family dynasty. But by the 1960s the traditional Downtown elite, mostly Anglo and Protestant by heritage, had lost some of its historical wealth and relative status in the city to upwardly mobile groups with different backgrounds — such that Chandler was concerned that she might not be able to raise the requisite funds from this group alone. The fundraising efforts for the Music Center then were somewhat of a seminal effort in that for the first time the old ‘blueblood elite’ collaborated deeply with an outside group to pursue a common aim. In particular, per Fulton’s telling,

“Dorothy Chandler was the first downtown cultural figure to reach out across town to the other center of wealth and power in Los Angeles: Hollywood. She aggressively courted the ‘Hillcrest Country Club’ crowd—the wealthy Jewish circles with close ties to the entertainment industry—and secured major donations even though Jews were not allowed in the downtown clubs that served as her traditional power base.”

Successfully completed in 1964, the Music Center did attract patrons of the theater and symphony to venture Downtown, but this population of attendees was decidedly too small in number and infrequent in visitation to inject sustained after-hours vitality to DTLA. And as soon as the curtains closed, these patrons of the arts promptly returned to their cars and drove decidedly away.

The Music Center was not alone among major mid-century projects to reshape Downtown Los Angeles. Indeed, throughout the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s a number of DTLA residential neighborhoods were cleared as ‘slums’ to allow for new development — most infamously this was the case with the old Victorian mansions of Bunker Hill. Additionally, redevelopment agencies razed a number of historic buildings specifically to build parking lots, with the rationale that in order to compete more effectively with the suburbs, Downtown LA needed suburban-style parking. These mid-century efforts did permanently alter the face of Downtown Los Angeles; but they certainly did not bring the urban vitality they had aimed for, nor did they incentivize meaningful numbers of people to move into Downtown Los Angeles as permanent residents.

“The Olympic Renaissance”

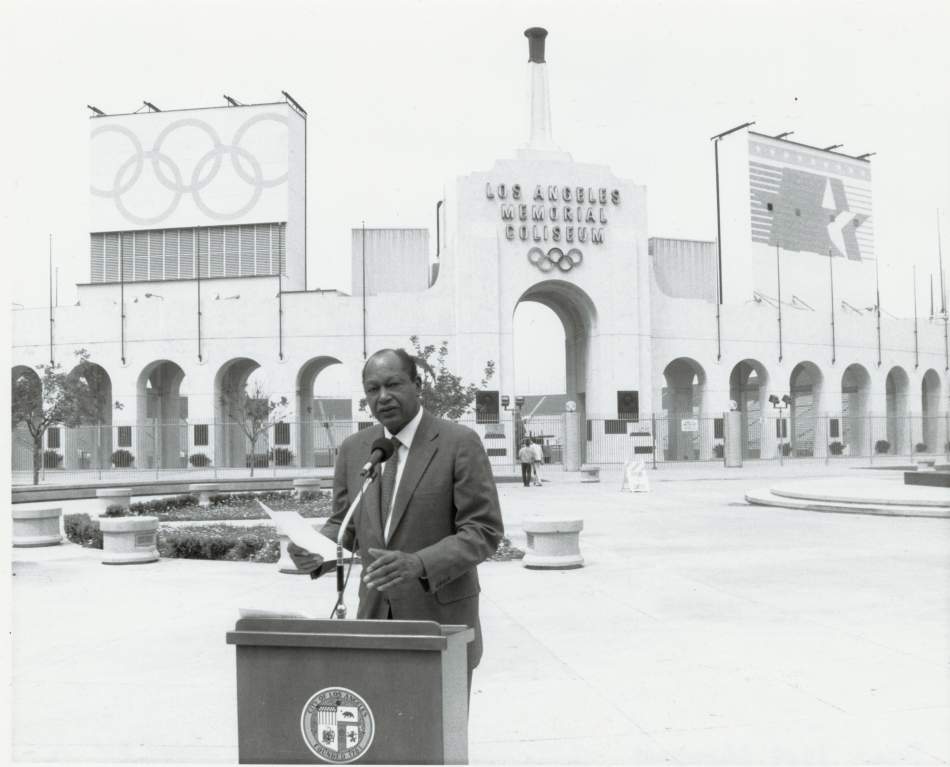

But the private and public redevelopment efforts of the ‘60s and ‘70s were seemingly only a prelude to the city-sponsored growth that was to come to DTLA through the 1980s. Over the decades following from WWII, Los Angeles had grown to a population size, economic capacity, and cultural center status that put it on the world map. In certain respects, LA’s cultural impulse during the 1980s was to announce to the world that LA had ‘arrived’ as a major global city — with the 1984 Olympic Games serving as its debutante ball. The public figure most closely associated with this public image of Los Angeles during that time was Mayor Tom Bradley, and one of his major policy objectives throughout the 1980s was the encouragement of skyscraper development Downtown.

The 1984 Olympic Games, for which Mayor Bradley was a major champion, served to focus the world’s attention on Los Angeles in a way that had seldom been rivaled in the city’s history. Contra the abundant doomsday predictions, the 1984 Olympic Games have widely been considered quite successful, and they presented the city very positively. Requiring no public contribution and running at a $222.7 million surplus, the 1984 LA Olympic Games brought more than $3.3 billion to the local and state economy, and over 74,000 Olympics-related jobs. In the fashion typical for a host city of the Olympic Games, in anticipation Los Angeles made major investments in its airports and other infrastructure. Capitalizing on the attention brought to the city during this time, Mayor Bradley and other political actors set about encouraging domestic and foreign investment in office skyscraper development Downtown, working in close partnership with developers to subsidize development via local tax increments and to overcome bureaucratic hurdles.

Why was Mayor Bradley so supportive of this sort of development, where little of the sort had existed in DTLA previously? For one, Mayor Bradley thought that the existence of skyscrapers would serve to attract businesses to Los Angeles, believing that businesses desired the prestige of these sorts of buildings and especially the opportunities to put their names on lighted signs atop them. A Democrat with an agenda focused on social services, Bradley was also known to be perhaps surprisingly business-friendly. As Mayor Bradley saw it, businesses generated tax revenue, which could then be spent on social services, so it was in his interest to ensure the viability of tax-paying businesses in LA.

The other reason Mayor Bradley supported skyscraper development was more nebulous: LA had ‘skyline envy’, and major political figures (including Bradley) wanted to encourage the development of skyscrapers in Downtown LA to signal to the world that LA had ‘arrived’ as a major global city. Of course, this rationale was rarely articulated outright in public statements or anything of the sort. But all of the sources I have spoken to about this topic who were intimately involved with LA city politics during this time period assert that the signaling component was of deep importance. The defining image of a major global city was an impressive, vertical skyline. Though LA did not have one at that time for rational economic and geographic reasons, as described in the Introduction, the political and social elite of Los Angeles during the 1980s were set on making LA’s global city status abundantly clear, and so LA needed an impressive vertical skyline too.

This sort of reasoning behind public policy on its surface may sound vapid and trivial, but dig a bit deeper and there could well be an economic rationale for this sort of signaling behavior. The surface level perception of global prominence may be an effective “booster” mechanism for attracting capital and people, which can then be put to use developing legitimately profitable industries. Because of these efforts, DTLA ‘looks the part’ of a major urban core, which I would posit plays a meaningful role in shaping the uneducated perceptions of the place for potential residents and businesses.

Laying the Groundwork for a True Downtown Renaissance

LA’s political elites in the ‘80s knew, of course, that building towers alone would not make DTLA the center of the region and the thriving ‘commercial capital of the Pacific Rim’ they so desired. As the decade neared its close, the Downtown skyline had been transformed, but then the real work was to begin. Looking toward the coming century, Mayor Tom Bradley assembled the “Los Angeles 2000 Committee” of “more than 150 civic and business leaders representing many constituencies and perspectives” to establish a sense of what LA had become and what should be its future. This Committee published its Final Report in 1988. Finding a consensus opinion for the future of LA amongst a fairly diverse set of stakeholders was naturally going to be a challenge. Recognizing the scale of Los Angeles, however, the Committee was able to advocate in unison for greater regional governance — as the Report states, “pollution, crime and traffic jams are no respecters of city limits.” Transit immobility was also one of the primary challenges the Committee sought to address, and it advocated for the creation of a robust regional rail-based transit network. Looking toward the economic future of the metropolis, the Report also advocated for the creation of enterprise zones in jobs-poor neighborhoods.

To achieve these aims, the Report essentially advocated for a much more forceful regional planning agency that could corral the various local governments into coordinated action, for the sake of improving the region as a whole. A regional umbrella organization, the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) already existed, but it was largely toothless in enforcing its vision. The LA 2000 Committee planned to give SCAG some teeth (and to rename it the Southern California Association of Governance). Alas, many of the lofty hopes and ideals contained in this Report would be made to look foolish in the face of the calamities that would hit the city over the subsequent five years, to be addressed in the next chapter, so the Report did not immediately lead to many direct and successful actions. It does, however, provide a good insight into the mentality of the city’s elites during the late ‘80s, and it is striking in that many of its recommended strategies were in fact adopted by the City and County, but only about a decade after publication.

Returning to the question of LA’s future five years later, in 1993, LA’s political and business elites had been humbled somewhat by the extent to which the previous five years had been a disaster for the region, so they had to refine their vision for the city. This new vision was expressed in the 1993 Downtown Strategic Plan, prepared by the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles with significant input from a similar cross-section of LA business leaders. While the LA 2000 Committee had focused on regional integration as a whole, by 1993 this aim appeared overly ambitious, and so the city focused on an area it could better control: DTLA. Notably, the plan proposes for DTLA to rise as the center of a “Fifth Los Angeles”, and outlines a vision of the city’s past, present, and future strikingly similar to the one put forth in this paper, but written 24 years earlier at a point when that “Fifth Los Angeles” really was just in the imagination of the city’s planners. To clarify, that “Fifth Los Angeles” the Downtown Strategic Plan speaks of is analogous to the LA 3.0 put forth in this series, the main difference in nomenclature being that the Downtown Strategic Plan acknowledges “First” and “Second” LAs that existed before the 1890s when the region contained little more than small towns.

To reach the idyllic vision this document sets forth for a vibrant Downtown at the heart of a “Fifth Los Angeles”, the Downtown Strategic Plan identifies the various challenges DTLA faced in the early ‘90s (there were many) and proposed potential solutions for each. Seemingly, many of the prescriptions set forth in this document were put into action. For example, the Plan emphasized the importance of clean and safe streets, and called for the creation of community policing and neighborhood watch bodies. This rationale presaged the creation of Downtown Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), quasi-governmental neighborhood agencies for the various DTLA neighborhoods that employed street security officials and regular clean-up crews, in addition to encouraging businesses to locate in their districts. The actions of these BIDs are often hailed as an unglamorous but indispensable aspect to facilitating the DTLA development renaissance.

Notably, the Downtown Strategic Plan also called for the renovation and use of historic DTLA buildings, and proposed policies to advocate toward that end. Today, historic buildings used for apartments and offices are often considered fashionable, but this was less the case during the time in which the Plan was written. As Dan Rosenfeld puts it, many used to say “Why clean up a dirty old building when we can build a nice new one?” Rosenfeld, a real estate developer by career background who in the ‘90s went on to run the State of California’s Real Estate division within the Department of General Services, was tasked with investing $1 billion of the state’s money every year to support state employees’ office needs. During the early ‘90s, the State of California had determined that it needed more office space in which to locate its employees in Los Angeles. The state government, throughout this time under Republican control, had recently completed the massive Ronald Reagan State Office Building in Downtown Los Angeles. The state sought to expand its LA office presence further, and so Rosenfeld was charged with constructing a brand new “Nancy Reagan” sister building somewhere in DTLA — or even more preferably somewhere out in the suburbs, where most Republicans’ constituents lived. Rosenfeld, a Democrat, was less-than-thrilled with the working name for the building, and as an individual with personal beliefs in the benefits of vibrant urban cores and in the value of historic buildings, Rosenfeld had a different vision for the future “Nancy” building. He was able to demonstrate, against a fair degree of skepticism from others in state government, that renovating a historic building Downtown could be more cost-effective than building a new one either Downtown or in the suburbs. As such, he was able to convince the cost-cutting Republican state administration to support his historic adaptation plan, and so the Junipero Serra State Office Building opened in 1995 in a former department store in DTLA’s Historic Core neighborhood. This development is important in that it did a lot to establish the model for future adaptive reuse activities in DTLA, which would come to be a critical catalyst to the development boom. It was also important because it prevented a potential exodus of state employees from daily work in DTLA, a meaningful share of Downtown’s labor force, had such a facility been constructed in the suburbs.

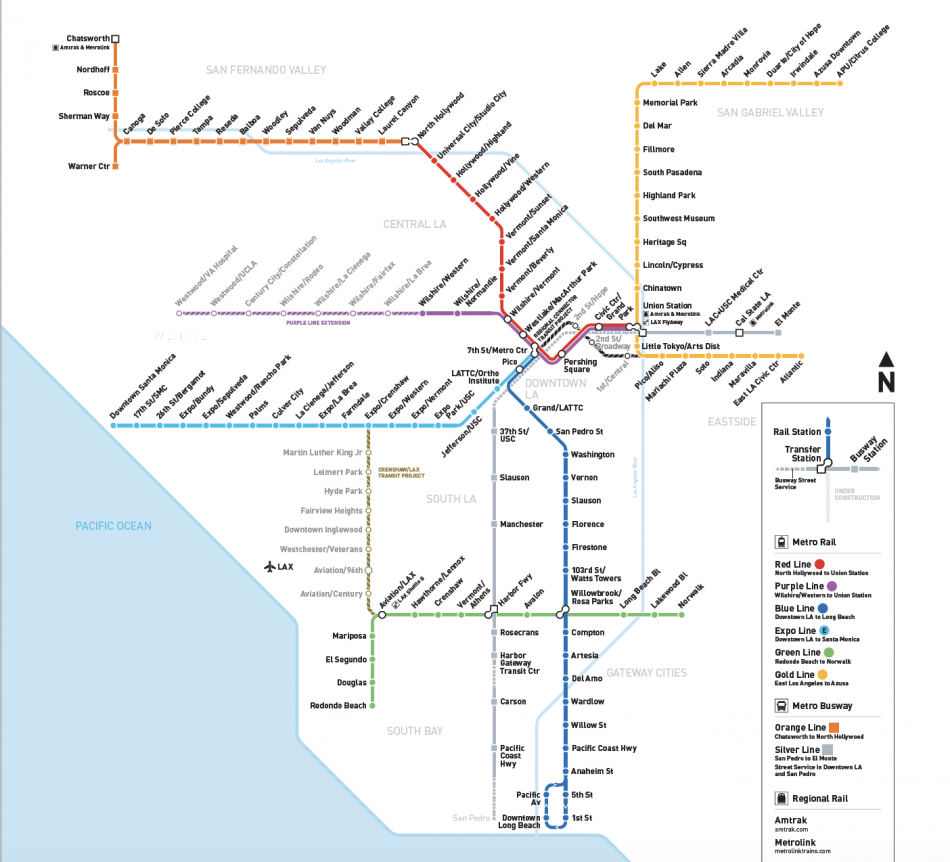

It would take an even more ambitious government plan, however, to put DTLA on the right track toward future growth and regional prominence. In a fashion that seems antithetical to everything people typically think about Southern California, LA County has over the past couple of decades set about constructing a fairly extensive public transit network. Los Angeles did not really build any modern fixed-rail transit lines until the ‘90s, and even that early development was sluggish and unpromising. In more recent years, transit development has been moving with more vigor: there are now seven different subway and light rail lines, all are being expanded, and many additional new lines are funded or even under construction. Critically, this entire network of transit infrastructure is centered on DTLA as its hub. In a city so plagued by automobile traffic, the promise of an easy commute offered by living at the heart of an efficient transit network surely bolsters Downtown’s appeal for residents, thus raising demand for housing in the area and incentivizing developers to build there.

These past two installments have addressed a number of the economic and political forces that coordinated to make the current building boom in LA’s urban core more likely. Over the past couple of decades, economic and population growth in LA have picked back up after a series of negative shocks in the 1990s. But this occurred against a new political backdrop which has been generally opposed to the development of new structures for housing and office space in the region’s most desirable neighborhoods. In response to this constraint, developers have needed to seek out new neighborhoods in which they can build and supply that demand, and the oppositional barriers have been lower in urban core neighborhoods such as Downtown, Koreatown, Hollywood, and surrounding areas. In addition, influential government officials and socialites have promoted Downtown LA as the center of the region, and encouraged cultural, commercial, and infrastructural development that would serve to distinguish it as such. But all of these forces had been unfolding over the span of decades, without sparking the same type of boom that we are seeing today. It would take a concurrent cultural evolution, executed largely in response to the manifest failure of the previous system, together with a pair of specific governmental actions both executed in 1999, to spark the boom in actuality.

Previous installation: Local Growth Politics and Development Patterns

Jason Lopata works as a land use consultant with Craig Lawson & Co., LLC, helping real estate development projects in LA navigate the city approvals process. Jason previously spent time on the Business Team of LA Mayor Eric Garcetti. He also writes articles on globalization and urban development for Stratfor, the geopolitical analysis website. Jason received his bachelor’s degree from Stanford University and completed programs of study at the University of Oxford and at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. While at Stanford, he founded and led the student real estate organization, and authored his senior thesis on Los Angeles development over the past 30 years.