Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, is back at it again with more outlandish ideas to solve Los Angeles' traffic. Earlier this month, Musk's latest venture–The Boring Company–resuscitated its flawed proposal to dig new car tunnels for Los Angeles, this time to connect the Red Line subway with Dodger Stadium. Last year, I broke down The Boring Company's proposed underground highway network and explained why it was an ill-conceived concept that would not achieve its stated goal of traffic reduction. At the time, Musk talked about how The Boring Company could reduce tunneling costs, but failed to specify how. Since then, The Boring Company has announced that it intends to build an express airport connector in Chicago, and now the Dodger Stadium link. The Chicago tunnel idea is bad enough, but the Dodger Stadium plan is exceptionally poor even if one takes Musk's promises at face value.

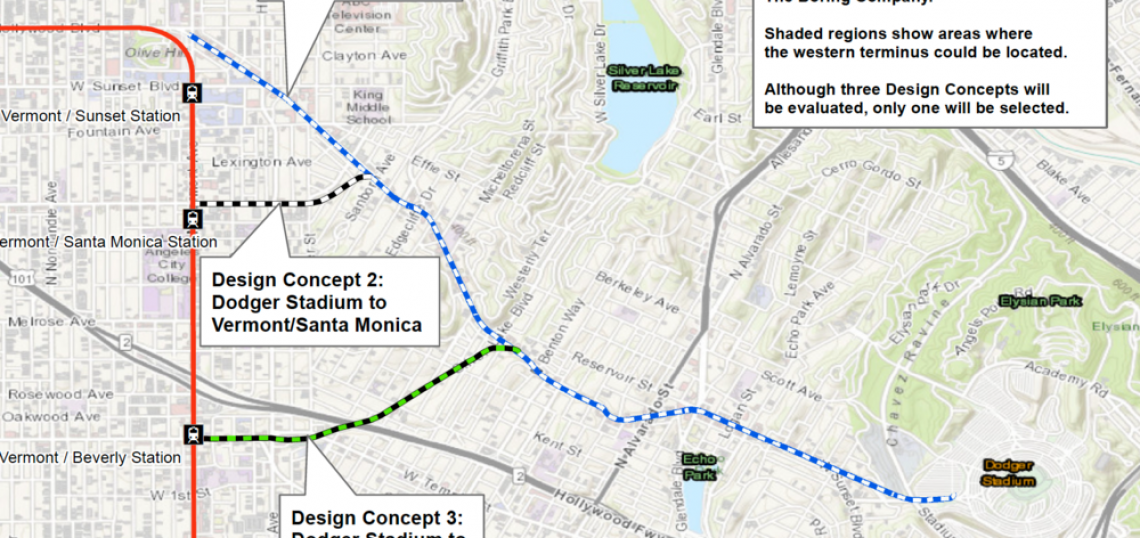

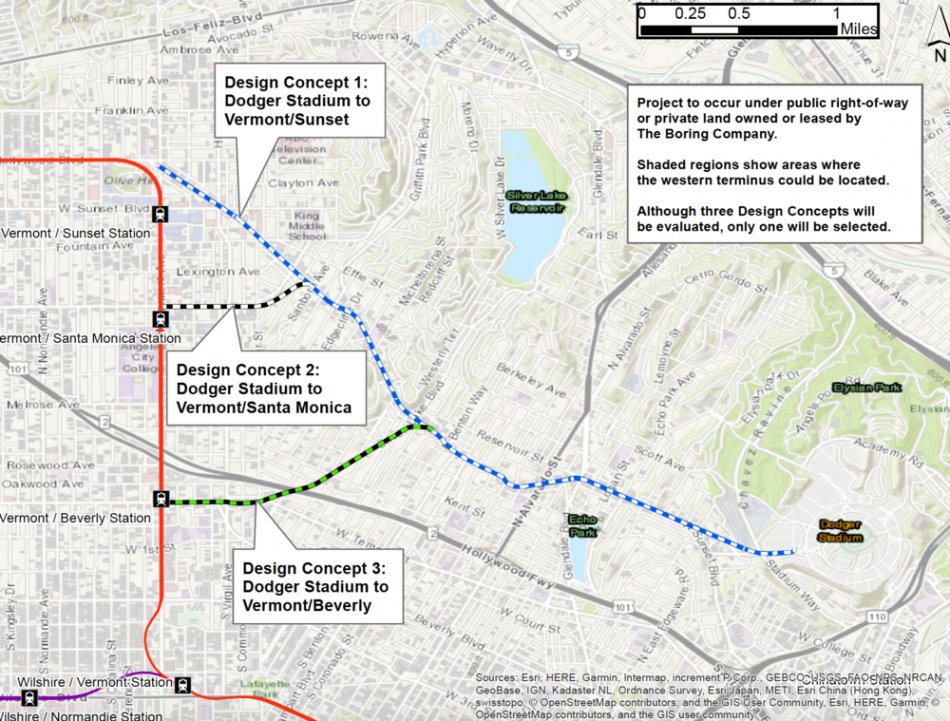

Musk's plan is to tunnel under Sunset Boulevard between the stadium and one of three Red Line stops: Vermont/Sunset, Vermont/Santa Monica, or Vermont/Beverly.

Can Boring deliver on its promises of cheap tunneling?

The Boring Company promises to drastically reduce tunnel construction costs. However, as we reported last year, there is little chance it could do so. Its estimates of low costs are based on assumptions and incorrect data, contradicted by professional engineering literature.

Last April, Forbes quoted MIT professor Herbert Einstein, who studies tunnel engineering and construction, saying that nothing about Boring's tunneling methods looks innovative. Only the vehicle design is novel—but that's not the source of most of the cost of construction. According to Einstein, he offered Musk some help with estimating costs based on his research, but never heard back.

In high-cost cities like New York, three quarters of the costs of subway tunneling come from the stations, and not from the tunnels between them. Boring's proposed tunnel would run between 3.1 and 3.6 miles nonstop (depending on the chosen alignment), which in theory would reduce the cost of construction, since there would be only two stations over this long stretch. Moreover, the Dodger Stadium terminal has so much space thanks to the large parking lot that digging a station should not be difficult. However, the western terminus at the Red Line is not an easy location for a station; the area is among the densest in the United States outside New York, and there is only room directly under the streets.

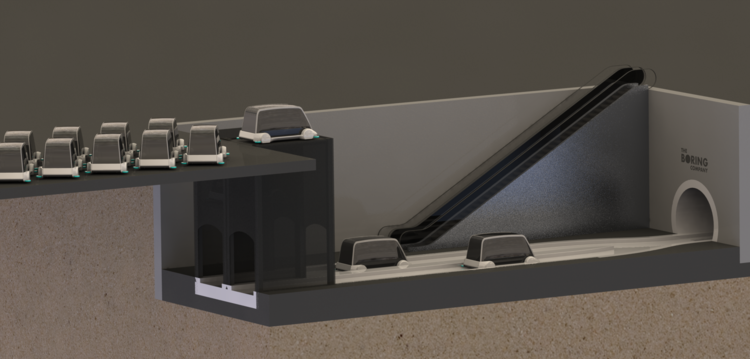

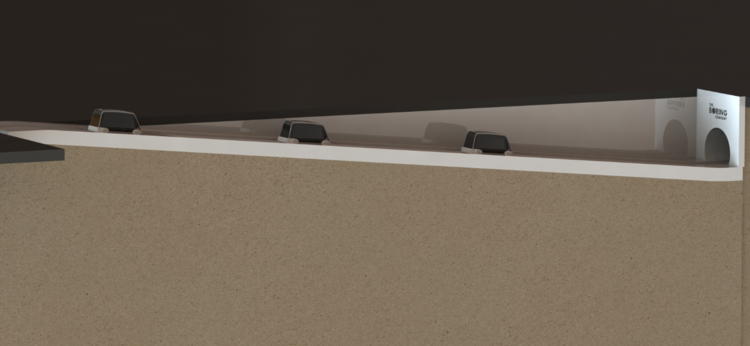

A conventional subway could open up the street to build a station. This would annoy nearby residents and merchants, but only take about 18 months and cost perhaps $100 million to construct; Paris is extending its Metro into dense inner suburbs using this method. However, Musk claims to be building more than just a subway tunnel. He wants to use small skates (carrying cars on top) going through the tunnel at very high frequencies (high enough to appear on demand, not scheduled), instead of a full-size train every few minutes. The proposed high-frequency service complicates the terminals, requiring more complex construction at Vermont Avenue, where there is no room for it.

Is there enough capacity?

By Boring's own admission, the line would only have enough space for 2.5 percent of Dodger Stadium's capacity. The small tunnel diameter and very small vehicles ensure that capacity would be limited from the start with no room for expansion.

In general, Musk has struggled with scaling up to the mass market. While the Tesla Model S sells well for a luxury car, the Model 3 has been beset by problems with missed deadlines, poor workmanship, and limited production rate. Tesla did not lose so much money when it was making luxury cars, but as it's tried to expand to the mass market, its losses surged to $700 million last quarter.

Boring claims that it would charge a dollar per ride on the tunnel. It is not aiming at a low-capacity first-class market, at least not officially. But it is not aiming to build sufficient capacity for a large fraction of Dodger Stadium's attendees, either.

One problem with the proposal is transfers with the Red Line. The Red Line runs full-size subway trains every 10 minutes at peak frequenices and every 12 minutes off-peak. Passengers going to the stadium wishing to transfer from the subway to Boring's small skates would have to queue. On such a short line, a few minutes of queueing add up to a considerable portion of travel time.

But more generally, serving sports events by any mode of transportation is inherently difficult because of what happens when the game ends. A transportation system designed around peak rush hour travel may still struggle with serving a ballpark. An ordinary rush hour may dump several tens of thousands of passengers into a city center per hour from each of many different directions, requiring either enormous freeways as in Los Angeles or many subway lines as in more transit-oriented cities of the same size. But when a game at Dodger Stadium ends, 56,000 fans attempt to leave the field all at once, a traffic surge that would stress any transportation network.

The problem is not unsolvable. A subway line would serve the stadium in at least two directions. Subways are also designed around very high crush capacity, provided passengers are willing to squeeze in. The ride is uncomfortable on the most crowded segment, but it gets people to where they want to go without making them wait an hour in traffic.

However, Musk shows little attention to capacity. The Boring Company proposal sticks to its proposed small-diameter tunnel, even though the cost savings from reducing bore size are limited. It sticks to its proposed skates rather than changing the plan to full-size trains; it considers connecting the skates together to form long trains to be an option to investigate rather than the only reasonable way to run service in a congested urban tunnel. A mass transit tunnel to Dodger Stadium would be an interesting proposition to consider, but it would not look like what Musk wants to build.

Is this even the right alignment?

Dodger Stadium is three miles from Vermont Avenue, but it is much closer to another transportation center: Union Station. Los Angeles' historic passenger rail hub is only 1.2 miles away, and is served by not just the Red and Purple Lines, but also the Gold Line, Metrolink, and soon the Regional Connector. Dodgers fans live all over the region, not just near the Red Line.

Sometimes, design compromises force a subway line to offer less than optimal service to a regional destination like a stadium or an airport. LAX is only served by the Green Line (with a shuttle bus connection), and though light rail is under construction along Crenshaw Boulevard and in planning along the Sepulveda Corridor, there are no plans for a direct connection to Downtown Los Angeles. However, Dodger Stadium is so close to Union Station that a back-and-forth tunnel could just go north-south connecting the two. Even the proposed aerial gondola, another low-capacity gimmick that has no business connecting to a sports arena, does this right and connects the stadium to Union Station.

Urban transit requires delicate systemwide thinking. Every urban tunnel should aim to be maximally useful for as many travel markets as possible. Dodger Stadium-Vermont is not really useful except for those traveling from Hollywood or North Hollywood to Dodger Stadium; the tunnel would be unused except for a short period before and after a Dodgers home game. It might be useful to Musk as a proof of concept in the unlikely event he can fulfill his promise of cheap construction, but it cannot make money with such low utilization.

In contrast, a multi-stop conventional subway tunnel along the same route could be a strong transit corridor. It would connect Dodger Stadium with Union Station to start with, filling up with baseball fans before and after home games; at rush hour it could turn the stadium into a remote parking lot for downtown workers (or, eventually, California High-Speed Rail passengers who are poorly served by Metrolink or Metro Rail). It would not get all-day usage, but could still provide more a connection to Vermont Avenue.

Eventually, it should be a subway line under Sunset Boulevard, connecting Hollywood with Downtown. Right now the Red Line provides such a connection, but a South Vermont subway line may one day sever this alignment, requiring passengers to transfer to the Purple Line at Wilshire/Vermont Station.

All of this depends on far future estimates of ridership growth, which in turn require extensive redevelopment of the low-density residential areas of the Westside. If a variant of the failed SB 827 bill succeeds in a future state legislative session, it would permit high-density mid-rise housing within walking distance of Metro Rail and many bus routes, providing the area with the ridership with which to support additional subway tunnels.

Should Los Angeles give the Boring Company a permit to dig under Sunset?

It is extremely unlikely that a tunnel between Dodger Stadium and Vermont would succeed, even if issues around Musk's grandiose overpromises were resolved. Worse, it would be hard to retrofit such a tunnel for conventional subway trains: widening the diameter of a metro tunnel is so hard that London is stuck with the small-diameter bores of the 1890s, which are capacity-constrained and have nowhere to get rid of excess heat.

The result is that the tunnel would have negative value to the region. As a transportation service based on how Musk wishes to construct and operate it, it has practically no value. But in the event of upzoning in West Los Angeles, the tunnel would complicate any possibility of rail under Sunset connecting Hollywood with Downtown. Metro may even need to acquire and demolish Musk's tunnel, or else dig under the tunnel, which would complicate intermediate stations in Silver Lake and Echo Park.

Both the tunnel's upside (the possibility of success) and its downside (so much Westside redevelopment a subway under Sunset would be warranted) are remote, but the downside outweighs the upside. There is going to be extensive demand from some of Musk's fans to expedite regulatory approvals to accede to Boring's wishes, but Los Angeles should resist such pressure and prohibit the use of Sunset as a private tunnel corridor. If Musk wants to bore tunnels, he should do so under private property and side streets and pay the owners a negotiated fee rather than getting access to a potential metro corridor.

Alon grew up in Tel Aviv and Singapore. He has blogged at Pedestrian Observations since 2011, covering public transit, urbanism, and development. Now based in Paris, he writes for a variety of publications, including New York YIMBY, Streetsblog, Voice of San Diego, Railway Gazette, the Bay City Beacon, the DC Policy Center, and Urbanize LA. You can find him on Twitter @alon_levy.