If every jurisdiction in California addressed housing the way the City of Los Angeles has over the past few decades, the state would have nothing close to the crisis we have today.

In Los Angeles, planning case timelines are some of the fastest in the state. Unlike other jurisdictions, the City has honored state laws that mandate cases that conform to zoning be approved. Historically, fees have been low. The processing of permits and inspections are better than any jurisdiction I have worked in during my career. And while most of the City’s zoning plans are outdated, the City has always been open to common sense zone changes and off menu density bonus incentives.

While the cost of housing is too high and continues to rise, Los Angeles still has a number of working-class neighborhoods. Rent here is still a fraction of what it is in San Francisco. This is the result of the City’s commitment to housing production; it has been a wonderful place to do business.

Anyone who drives in Los Angeles can see construction is happening at a rate we haven’t seen in ages. But the construction you see is a “lagging” indicator. These projects were approved under the policies of years past.

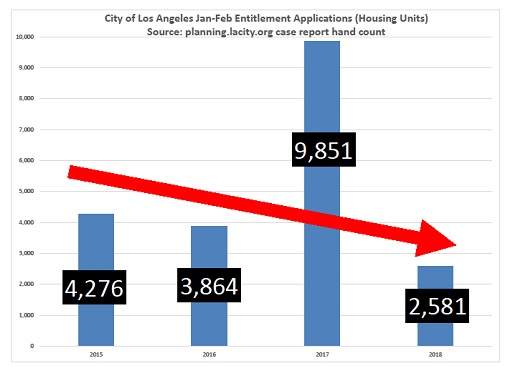

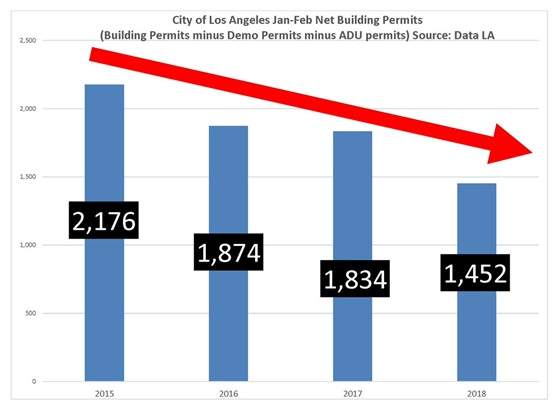

Starting two years ago, things started to change in the City. A series of policies were enacted that have made it much more difficult to create housing. Recent data of “leading” indicators are showing new housing projects are dropping off in the City. Take a look at the year-over-year charts for housing unit entitlement applications and net new building permits.

The above chart shows the number of proposed housing units submitted to the Planning Department for entitlements every January and February for the last four years. Since submitting a case for entitlements is the first step for all of these discretionary housing projects, it is the best “leading indicator” of how new policies will produce future new housing in the coming years. Ignoring the outlier year of 2017 (I will explain later), you can see units are down 40 percent from 2015 to 2018.

Above you see a chart of net building permits from the January and February period from the last four years. I define “Net Building Permits” as building permits minus units receiving demolition applications minus building permits for accessory dwelling units. This creates an apples-to-apples comparison of how housing policy is creating new housing units. After entitlement applications, this is the second best leading indicator of how policies are creating housing. You can see that in 2018 new building permits are down 33 percent from 2015.

How are these two charts possible? Our economy is in decent shape and, elected officials in Los Angeles are committed to bringing new units to market. Median home prices and rents in Los Angeles are the highest they have ever been, and we are in the middle of a crippling housing crisis. Given these conditions, entitlement applications and building permits should be rising, not falling. Below I will describe the four main reasons for this drop-off.

Affordable Housing Linkage Fee and the Increased Park Fee

In 2015, I paid $35,906 per unit in fees for a project I built in Los Angeles. Today, that project would cost $61,118 in fees.

Last year the City adopted an ordinance increasing Quimby fees, which are used to generate money for park construction. While Los Angeles needs more green space, I don’t understand why homebuilders in a housing crisis are expected to pay for them.

In December, the City adopted an Affordable Housing Linkage Fee Ordinance of an average of $12 per square foot for new construction (Up from $0). The City absolutely needs a local source of funding to contribute to the capital stacks of affordable housing projects. Taxing new home construction, one of the last remaining manufacturing businesses left in the country, is not the appropriate way to do it. This policy will create less net housing, not more.

These two new fees have lowered residual land values. Housing builders now have less purchasing power to compel a cash flowing Los Angeles land owner to sell. To put it bluntly, these two fees have made it extremely difficult to develop any housing in Los Angeles that is not dense enough to take advantage of the City’s density bonus ordinance. While the linkage fee passed in December 2017 and won’t fully vest until the end of the year, the development community has been expecting the fee for over two years. Since we haven’t known when the fee would be enacted, it has already stopped many projects from getting off the ground.

These fees are the smallest of the four reasons for the drop off in housing creation. But as the linkage fee vests to its full amount in the coming months it will become even more of a damper on new entitlement cases and building permits.

Changes In The Expedited Processing Unit

One of the best parts about developing in Los Angeles is their expedited processing unit. Established in 2003, applicants pay an additional fee to receive a public hearing within 90 to 120 days of their case being deemed complete. Using this unit, I often begin construction - planning and building permit approval - inside of ten months from my initial application submittal. If a project wasn’t accepted into this unit, it would take - on average - an extra year to start construction.

Recently the City has become much more selective about what projects are accepted into the unit. Smaller projects, in particular, are not being accepted.

For an example of the practical nature of this policy change, consider that there are over 12,000 single family homes on land zoned for multi-family development in Los Angeles. New developments on these properties are good because they minimize displacement, and conform to zoning laws and the existing built environment. From a practical standpoint, most of these properties are 50-foot-wide lots. Depending on the lot, you can generally build four-to-ten units on these lots. If you want the project to be for sale, need a modest zoning adjustment, or want to use any on menu density bonus incentives (height increases and side yard reductions are common), you need a planning case. Since the Expedite Unit is not accepting these cases as frequently anymore, it will likely take you an extra year to start construction.

Small projects like this can’t bear the extra year of carry. The result is that the project just doesn’t get built. This is unfortunate because – as I’ve already mentioned - these projects minimize displacement and conform to the zone and neighborhood. They are generally three-to-five stories and offer cheaper rents than the so-called “megaprojects,” you see on commercial boulevards. As we run out of land, developments on these 5,000-to 8,000-square-foot, 50-foot wide lots will become more common. We should expedite their approvals.

Measure JJJ

Measure JJJ was passed by a vote of people in November 2016. Before this date, Los Angeles relied on zone changes to provide a material amount of the housing it delivered every year. Measure JJJ changed the process of how you process zone changes in the City. We can debate the positives and negatives of that process, but it doesn’t matter. What does matter is that fifteen months after passage, I am not aware of a single project under construction in Los Angeles processed with a zone change under Measure JJJ.

Starting in the summer of 2016 through the first week of March 2017, there was a massive increase in the amount of zone change entitlement applications submitted to the Department of City Planning. This sudden rush was to ensure that any proposed development could “vest” before the passage of Measure JJJ and Measure S. This is why the 2017 entitlement caseload in Exhibit 1 above is so out of trend. Last January and February several “moonshot” zone change cases were submitted before the March 7 election for Measure S, which would have banned zone change applications for two years. In these two months alone, there were 14 zone change projects sized over 90 units filed with the City, totaling 4,285 units. As of today, none of these projects have been approved. Considering how ambitious they are (each project averages over 300 units), it is likely that only a fraction of them will ever break ground.

After the Measure S election in March 2017, entitlement applications have fallen off a cliff. No one has successfully figured out how to process zone changes under Measure JJJ’s new rules. This is especially sad for the large amount affordably priced workforce-style housing in the San Fernando Valley that was abundantly processed with zone changes.

Entitlement units are down 40 percent in 2018 compared to 2015. This is in line with the entitlement activity post the Measure S election. Absent a dramatic change in land use policies, I do not see unit counts returning to 2015 levels, much less rising from it.

Inappropriate Community Plan Updates

This is the biggest reason for the drop off in new housing creation. Measure JJJ would be irrelevant if the City had appropriate zoning capacity to create housing. Los Angeles has run out of properly zoned land to create housing. As of 2017, Los Angeles has a population of just over 4 million people, yet its total zoning capacity is for just 4.3 million people.

To address this, in 2015 the City began the process of updating its community plans. In 2015 new community plans were adopted for Granada Hills and Sylmar. This was followed in 2017 with new community plans for West Adams, South Los Angeles, Southeast Los Angeles, and San Pedro. The City has committed to a process that will update the remaining 29 plans in the coming years, which is good. What is not good is that the zone changes in the six adopted plans do not create opportunities for new housing in any meaningful way. Judging from the drafts of future community plans, I do not see this trend changing.

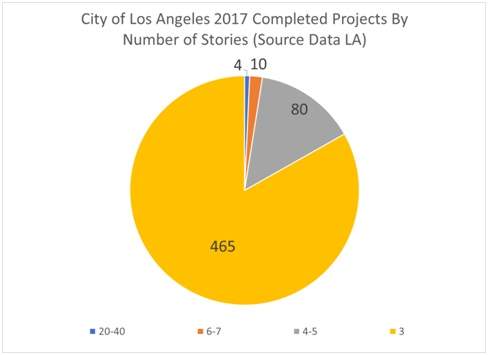

To understand why this is happening, we need to look at what kind of housing makes sense in Los Angeles. The best way to do that is to study the heights of recently completed projects in the City. As the below two charts show, Los Angeles is a City with income levels that justify the creation of missing middle housing between three and five stories.

Los Angeles zoning allows six- and seven-story residential buildings on many commercially-zoned lots. For the commercial lots that do not have the zoning in place for six or seven stories, the City has historically allowed common sense zone changes and/or off-menu density bonus incentives to accommodate the height. It is interesting to note that despite this, only 10 residential buildings in all of Los Angeles were completed in 2017 sized six to seven stories. None were eight stories. Remember this the next time someone complains about proposed new state laws creating “six to-eight-story buildings everywhere.” They are legal today in Los Angeles today, but and are rarely built.

Why have there been so many more buildings completed in the three-to-five-story range than in the six-to-seven story range? The answer is simple: six-to-seven story buildings are far more expensive to construct. They are also far more risky to build. Los Angeles only has a few neighborhoods with the income levels to justify the rents needed to build complicated six-to-seven-story buildings. The City’s income level and demand can more easily support a sweet spot of residential buildings three-to-five stories in height.

Unfortunately, the City’s strategy to address population growth in community plan updates is to add floor area ratio, density, and height to commercially zoned lots. This often allows for buildings over six stories. The updates passed to date do not generally create new zones for three-to-five-story buildings where they weren’t previously allowed. The main reason for this is that the only areas left in the City to create this level of density are single-family and duplex zones.

The most unfortunate example of this dynamic is the Southeast Community Plan update. Several properties that did not previously allow residential or allowed mid-rise residential were upzoned to a 6.0 floor area ratio and unlimited height. A 6.0 floor area ratio property is typically a steel-constructed building of over 10 stories. This is the most expensive type of residential construction. I don’t understand why the plan chose to add this type of density in one of the lowest-income parts of the city.

Land that was upzoned in recent plan updates was immediately was priced for its maximum density. As a result, raw land in the upzoned areas of Southeast Los Angeles is often more expensive per square foot than suburban areas with double the rent. Just like in the Cornfield Arroyo Specific Plan area, landowners are patiently waiting for skyscrapers to pencil. We need housing today, and even if those potential high-rise buildings pencil out, they are not the price point of housing we need. Since these properties are priced for densities that are infeasible to construct, transactions are down. This is the main reason entitlement applications are down. There is no land left for the type of housing that makes sense to build, and plan updates are not creating any new land for this type of housing.

The dropoff in new housing opportunities will not pose an immediate threat to Los Angeles’s housing crisis. The City has a robust pipeline of already entitled units and units under construction. I expect certificates of occupancy in 2018 and 2019 to be the highest they have been in over a decade. It is housing deliveries in 2020 and beyond that I am concerned about.

As I see it, we have a difficult choice to make here. We can take the easy route; do more of the same and hope for the best. If it doesn’t work out, it becomes someone else’s problem in the future. Or we can look at difficult land use decisions to ensure an inclusive Los Angeles with economic opportunity for all.

I want to respond in advance to reasons I’m sure will come up to justify this data as not alarming.

This Sample Size Is Too Small

We only have two months of data for 2018. It is one-sixth of the data available from the last four years. The housing units submitted in 2018 for entitlement data is certainly representative of the drop off that started after the Measure S election. I don’t see that trend changing.

I cannot predict how building permits will do in 2018. The Planning Department approved a massive amount of housing units over the past few years, and expect many of those units to receive building permits in 2018. How that blends with permits that don’t need planning approval, that never receive permits because of increased fees, the lack of properly zoned land, and less expedited processing remains to be seen. If you don’t count accessory dwelling units, there were fewer building permits issued in 2017 than 2016. I predict 2018 and 2019 will have a similar amount of permits than 2017. The drop off should come in 2020. With our housing crisis, we should be increasing permits, not decreasing them.

Why Did You Omit Accessory Dwelling Units From The Building Permit Data?

Starting January 1, 2017, a new state law was passed making the development of accessory dwelling units (ADU) much easier than before. The law has been a tremendous success. In the first two months of 2017, 24 permits were issued for ADUs. By the first two months of 2018, that number was up to 485 permits. These permits are for a variety of different types of ADUs. Some were for the legalization of existing bootlegged units, some conversions, some additions, some ground-up construction.

I keep these stats separate for two reasons. First to show the tremendous success of the program. It is proof of how much housing capacity we can create by levering the abundant amount of single family zoning we have in Los Angeles. But second, ADUs should be used as a tool to create more housing, not as a supplement for lost units from poorly working policies.

The Recently Adopted Transit-Oriented Communities (TOC) Ordinance in Measure JJJ Will Fix This

Part of Measure JJJ was instructions for the Department of City Planning to create a TOC ordinance. The TOC ordinance was adopted in September 2017. Since then, a number of entitlement and building permit applications have been submitted using this ordinance. I don’t see this ordinance creating a material amount of net new housing, as the TOC ordinance is essentially a “super density bonus ordinance.” It does not create new housing opportunities on properties where they did not previously exist. Rather, in exchange for including below market rate housing, it allows an incremental amount of additional density. Every TOC project currently in the pipeline would have still been a project had Measure JJJ not passed. They just would have been a zone change or traditional density bonus project. The loss of units from zone changes after JJJ far outweighs any incremental additional units that the TOC program will allow.

Updating of the City’s 35 Community Plans Will Fix This

I do believe the upcoming update for the two community plans in downtown Los Angeles will create opportunities for new housing. After far as the other 33 plans, I am generally not optimistic. The City’s current strategy of planning for future growth, outlined above, is not working. New housing creation will come from the addition of zoning that creates three-to- five-story missing middle housing. Given that this would mandate the very painful process of upzoning some duplex and single-family zones, I am doubtful that this will ever happen on the local level.

--------

I do not expect local elected officials to materially fix this pattern, nor do I blame them. They serve their local constituents, and a great number of voters in their council districts are single family home owners who don’t want their neighborhoods touched. Passing new community plans that add density to these areas, or lowering development fees, are just not something I see as politically viable on the local level. Reform will have to come from the state.

For decades Los Angeles has been the shining star in the housing story of California. The jurisdiction that showed the rest of the state how to properly add housing in an infill setting at all income levels. It is depressing to see that star start to fade.

@housingforca is a Los Angeles based residential developer. Follow him on Twitter @housingforca. For inquiries, email housingforla@gmail.com