Downtown LA’s revival was kicked off by the passage of the Adaptive Reuse Ordinance and the opening of Staples Center in 1999, but in many respects the DTLA we know today is a product of the 2010s. The 2000s were primarily characterized by a flurry of loft adaptations Downtown, where underutilized old office and industrial buildings were converted into apartments. But for all of this activity during this period, the built environment changed little on the exterior. This article highlights two Downtown neighborhoods where the built environment has seen dramatic change over the course of the 2010s, with an eye toward how we may expect Downtown to evolve further during the 2020s.

Downtown Los Angeles was the original core of its massive metropolis, but during the latter half of the 20th Century it was marked by the departure of residents and cultural institutions, leaving much of the city center as a supersized office park by 2000. Downtown remained the largest regional employment center, but it had relatively few residents, stores, restaurants, or other drivers of pedestrian life after 5:30 PM. Its physical landscape was dominated by office towers and surface parking lots. Building booms in the 1970s and ‘80s had yielded an impressive skyline, albeit overbuilt from an office market standpoint, but few of the other uses that lead to a vibrant urban core at all hours.

By 2000, Downtown LA had begun its revitalization process in earnest. While its built environment in 2010 broadly resembled its appearance in 2000, still dominated by office towers and parking lots, the initial signs of a transformation were emerging. The first new residential towers had begun to open near Staples Center in the late 2000s. And the influx of new residents, who began moving into historic office buildings converted to lofts under the Adaptive Reuse Ordinance of 1999, created demand for retail and restaurants by 2010.

This process matured over the course of the 2010s. The lion’s share of these new high-rise developments were built this past decade as the country emerged from recession. Critically, whereas DTLA was a “Wild West” investment destination during the 2000s, in which most investors were entrepreneurs with a hearty appetite for risk, by the 2010s DTLA was a safe-enough bet that larger institutional investors were willing to enter the market. Their greater sums of investment capital can be seen in the larger buildings constructed Downtown over the past decade. Moreover, many of the historic office and industrial buildings Downtown had already been converted to residential lofts by the 2010s, so new construction was necessary to accommodate continued demand.

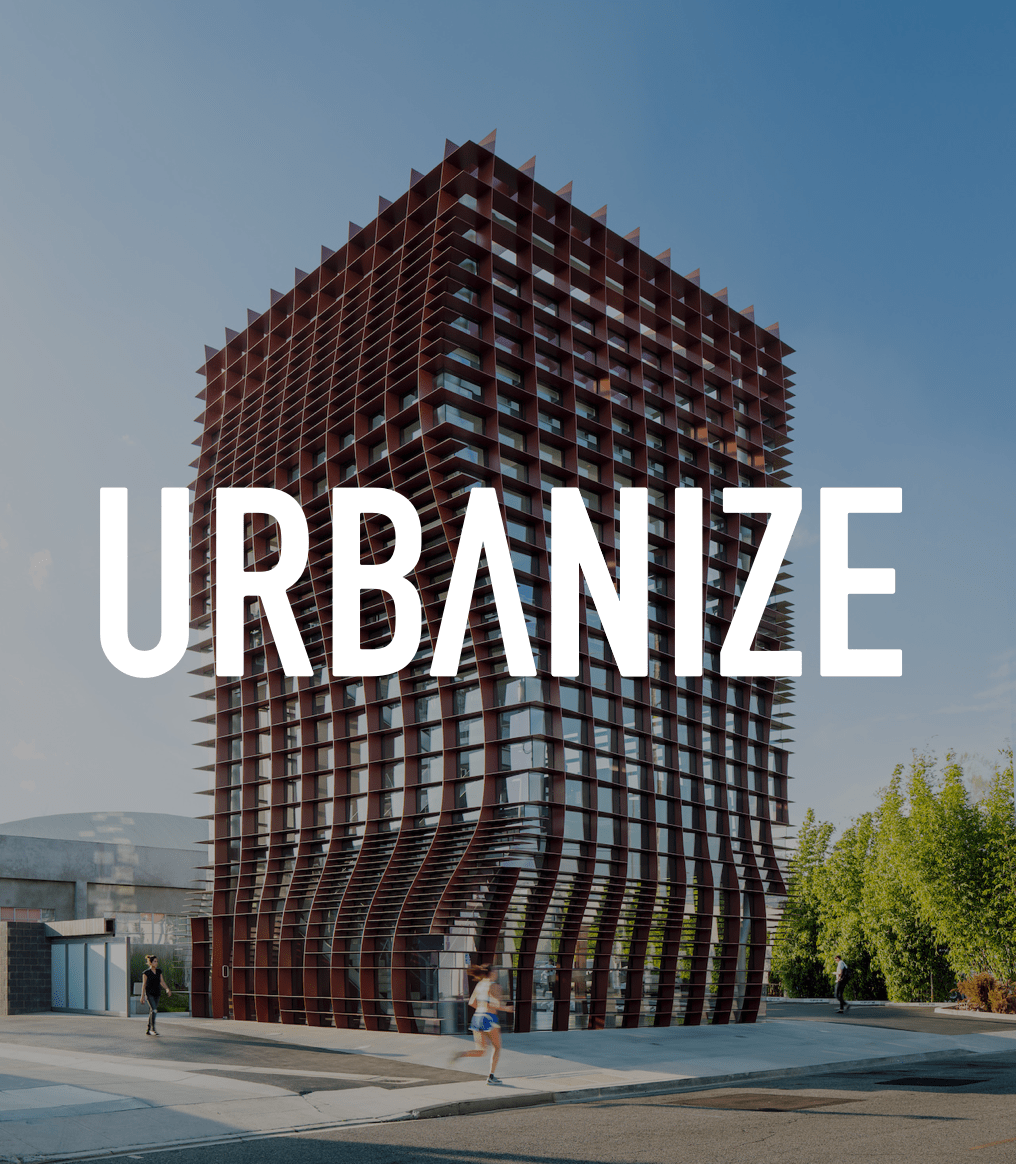

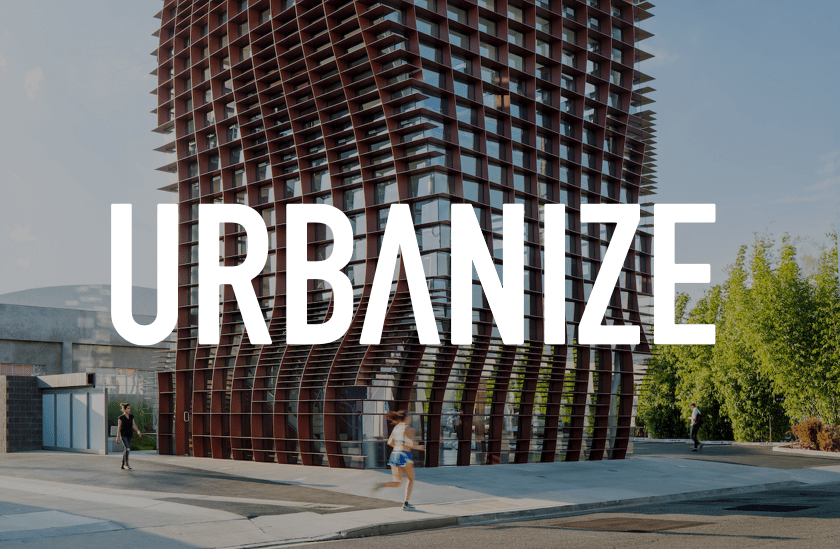

The deluge of investment Downtown has transformed several of its neighborhoods, but perhaps none more so than South Park, located near Staples Center. With an abundance of developable land, South Park has seen the bulk of the new construction Downtown this past decade. Its most attention-grabbing projects have been large Chinese-funded developments such as Metropolis and Oceanwide Plaza. But perhaps those with the most meaningful impact today are the many mid-rise and high-rise apartment towers that have proliferated throughout the neighborhood, constituting a major portion of the new housing built in all of Los Angeles over the course of the 2010s.

The 2010s also transformed the northern edge of Downtown. With the presence of the Civic Center, the Music Center, and the corporate office towers of Bunker Hill, DTLA’s north was already a hub for business, government, and culture. But these various fragments were not yet integrated into a coherent whole. As was the case across so much of Downtown in 2010, promising buildings could not realize their full potential as they were separated from each other by parking lot dead zones.

Development over the course of the 2010s has helped to fill in those gaps, and it has yielded an increasingly vibrant and coherent northern district. Redevelopment of Grand Park, the green fabric linking the various portions of this area together, commenced in 2010, largely funded by the Related Companies as a part of its Grand Avenue Project. But it has been mainly the The Broad Museum drawing people to this neighborhood. Attracting over 800,000 visitors per year, The Broad gives Grand Avenue street activity that spills over to its surroundings, as people incorporate a visit to the museum into a wider day’s journey to DTLA. Responding to the newfound pedestrian activity on Grand Avenue, the Music Center completed a renovation of its central plaza in 2019, opening it up to this suddenly vibrant street.

Over the years to come, the Bunker Hill / Grand Park neighborhood should continue to mature. Amongst other major projects, work should conclude over the next few years on The Grand, a mixed-use mega-development across the street from the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and on the Regional Connector subway line, providing this neighborhood with a Metro rail station adjacent to the Broad Museum.

Generally speaking, changes to DTLA’s built environment create a ‘snowball effect’. Parking lots and vacant buildings actively detract from the desirability of being Downtown. Each time one of those detractors gets replaced or reused, the benefit to Downtown’s desirability is double, because it has removed an undesirable force, while adding a desirable attraction. And as for people, whenever someone new moves Downtown, it makes the neighborhood more desirable to all of this person’s friends, as they now know another person who lives Downtown. With this process in mind, it is evident how the fleshing out of Downtown’s built environment, which took place largely in the 2010s, truly lays the groundwork for a mature Downtown to come in future decades.

Looking toward the 2020s, the main neighborhoods for development Downtown may begin to shift. Many of the best developable parcels in the southern and northern ends of Downtown have already been taken by now. So, developers and residents may begin to focus on areas that have not received much investment to date. Adaptive reuse projects in the 2000s created lofts in the DTLA Historic Core and Arts District. Such projects in the 2020s may create new residential enclaves in areas such as the Fashion District or South Park to the south of Pico Boulevard, areas which have yet to experience much residential growth. These areas, located a bit further from existing traditional job centers, will likely rent at a discount, accordingly making them more affordable than the central parts of Downtown, where prices have grown significantly over the past decade.

The main influence on Downtown’s built environment over the coming decade will likely be the DTLA 2040 Plan. The Los Angeles Department of City Planning is in the process of updating its Community Plans for the areas including DTLA, and it has released its draft plans on a dedicated website. Per this plan, DTLA would add about 125,000 new residents over the next 20 years, more than doubling its current count of about 75,000 residents. The plan seeks to accommodate this growth by rezoning portions of Downtown to allow residential use where it is not permitted currently. The bulk of this rezoning is to take place in the Fashion District and surrounding areas. If this plan is realized, it will have the effect of shifting DTLA’s center of gravity in a south-easterly direction, toward the Fashion District. Residents and cultural attractions would likely follow this population surge.

Jason Lopata is a Master of Real Estate Development (MRED) student at USC. Previously, he worked as a land use consultant with Craig Lawson & Co., LLC, helping real estate development projects in LA navigate the city approvals process, and he spent time on the Business Team of LA Mayor Eric Garcetti. He also writes articles on globalization and urban development for Stratfor, the geopolitical analysis website. Jason received his bachelor’s degree from Stanford University and completed programs of study at the University of Oxford and at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. While at Stanford, he founded and led the student real estate organization, and authored his senior thesis on Los Angeles development over the past 30 years.