We live in and among them. Much of the time, they are so familiar that they fade into the background. In other circumstances, we notice and celebrate them as a crucial part of Los Angeles. We even protect some of them as monuments to the way things used to be. But, paradoxically, we also ban them. What are they? They are our buildings, the places where we live and work and shop.

Welcome to the forbidden city that lies within Los Angeles.

L.A.’s forbidden city consists of the many buildings that we inhabit, use and care about but that are illegal to build today. Some of Los Angeles’ most iconic building types, from the bungalow courts and dingbats common in our residential neighborhoods to Broadway’s ornate theaters and office buildings, share this strange fate of being appreciated, but for all practical purposes, banned.

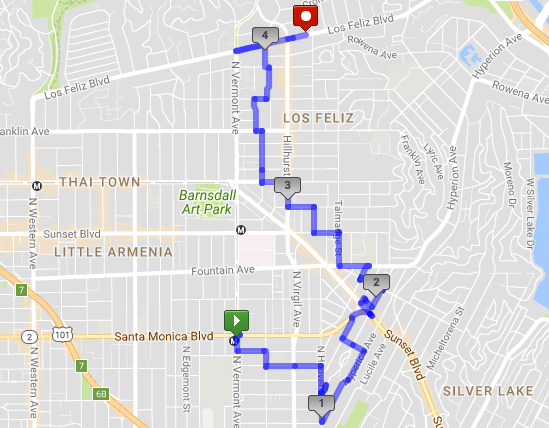

For a few years I have wanted to lead a tour to see and consider some of these forbidden buildings. The irony that much of our city is illegal to build today is an interesting facet of L.A.’s history. I also felt that wider awareness of why and how so much of our built environment became restricted could help us think about how to plan for the future. Thanks to the pedestrian advocacy group Los Angeles Walks, I finally got the chance to organize a Forbidden City tour in late July. Around 50 of us walked parts of East Hollywood, Silver Lake and Los Feliz to notice, pay respect to, and discuss some of the forbidden building that comprise these neighborhoods.

We could have done this walk in almost any LA community where there is a mix of pre- and post-World War II buildings. In fact, I chose the route partly because of it ‘ordinariness.’ We didn’t focus on building designed by famous architects or those with a noted history. The streets we walked had a mix of low-rise small and medium apartments, with a scattering of single family homes and a few commercial stretches. The policy history that I share below is tailored to these residential buildings. A somewhat different history and tour could be designed for other components of our forbidden city, such as the special rules that govern buildings in hilly areas; the shameful legacy of racist private and public restrictions on where people could live; limitations on more ‘naturally affordable’ dwelling like mobile home parks, residential hotels, and motels; and changing standards for commercial development. But for this walk, exploring how laws have impacted diverse types of multi-family homes seemed especially relevant given the severity of today’s housing crisis.

Origins of the forbidden city

The basic thesis of the walk was that changes to Los Angeles city zoning and building rules gradually banned many of L.A.’s most popular housing types. By cross-referencing several important policy changes with the style and age of buildings we saw on the walk, it was possible to trace the emergence of L.A.’s forbidden city. Each property and building provides a clue to the history and mystery of what happened to Los Angeles’ housing over time.

I should make two caveats before jumping into this history. First, I’m not trying to imply that regulation of the built environment is bad. Many rules have improved the safety and quality of housing. We wouldn’t want new homes today to be built exactly the same as how they were constructed in 1921 or 1961- any more that we would want motor vehicles in 2017 to lack seat belts or to be designed to use leaded gasoline. We should, however, be more thoughtful about how new rules might impact the homes we live in- and need more of. Second, the rule changes discussed below were part of a complex set of factors contributing to the evolution of buildings. Development practices, building cultures, land values, changes in lifestyles and demographics and other non-policy changes have all shaped L.A. We cannot pin all the blame (or credit) for changes to housing on our policies.

1908-1921

L.A.’s 1880s boom and bust generated Victorian style residences, but when the city started growing rapidly again in the early 20th century, bungalows were the most popular form of housing. In her chronology of Los Angeles architecture, Barbara Rubin noted that:

“The bungalow in Los Angeles was conceived originally as a detached single-family structure, appropriate to a region where residential space was both abundant and relatively inexpensive. Some locations remained undeveloped for decades, but others, adjacent to such amenities as beaches or commercial centers, sustained more intensive development… Bungalows in these impacted locations were constructed as multi-family dwellings in two basic configurations: as apartments houses, which required an expansion of the basic style; and as bungalow courts, which compressed the fundamentals into eight or ten separate miniature houses or “units.” Each solution, however, required no more land than had been previously allotted to the standard, single-family bungalows.”

Not everyone was happy with these new housing configurations. Robert Winter, in his book The California Bungalow recounts how “No less an authority than Charles Sumner Greene” [yes, of the Greene & Greenes] wrote in 1915 that “The bungalow court idea is to be regretted. Born of the ever persistent speculator, it not only has the tendency to increase the cost of land, but it never admits of home building… The style and design of each unit is uniform, making for the monotony and dreariness of a factory district. Added to this, the buildings are hopelessly crowded… This is a good example of what not to do.”

Greene’s complaints about speculation, mass production, and density have been echoed by critics of development and growth for a century. But in early 20th century L.A., there were not yet many barriers to building homes. Los Angeles was divided into residence districts and industrial districts between 1908 and 1909, making it the first municipality in the United States to essentially zone itself for use citywide. This division was the outgrowth of a wide variety of district ordinances adopted by the City Council in earlier decades to either outlaw or to permit uses like cow-keeping, laundries, cemeteries, saloons, brick manufacturing and other businesses considered by some to be nuisances in specific geographies within the city.

In residence districts the following noxious or loud activities were banned: “stone crushers, rolling mills, machine shops, planing mills, carpet beating, laundries/wash houses, firework factories, soap factories and other factories using other than animal power, hay barns, wood yards, lumber yards and feed stables.” Note that these residence districts - the distant ancestors of all of our zones and of our sometimes desire to separate, protect and exclude - still allowed all types of housing and nearly all types of retail and commercial establishments to co-exist on the same piece of property or next-door to each other. As a result, the only type of housing explicitly forbidden by this first zoning system would be dwellings in residence districts co-located with the specific industries listed above.

In addition to the public, district-based zoning system, there was a parallel private system of deed restrictions and covenants on many properties. These frequently restricted ownership to whites, and, in some subdivisions intended as ‘high class residences’ sometimes banned or limited multi-family buildings.

1921-1930

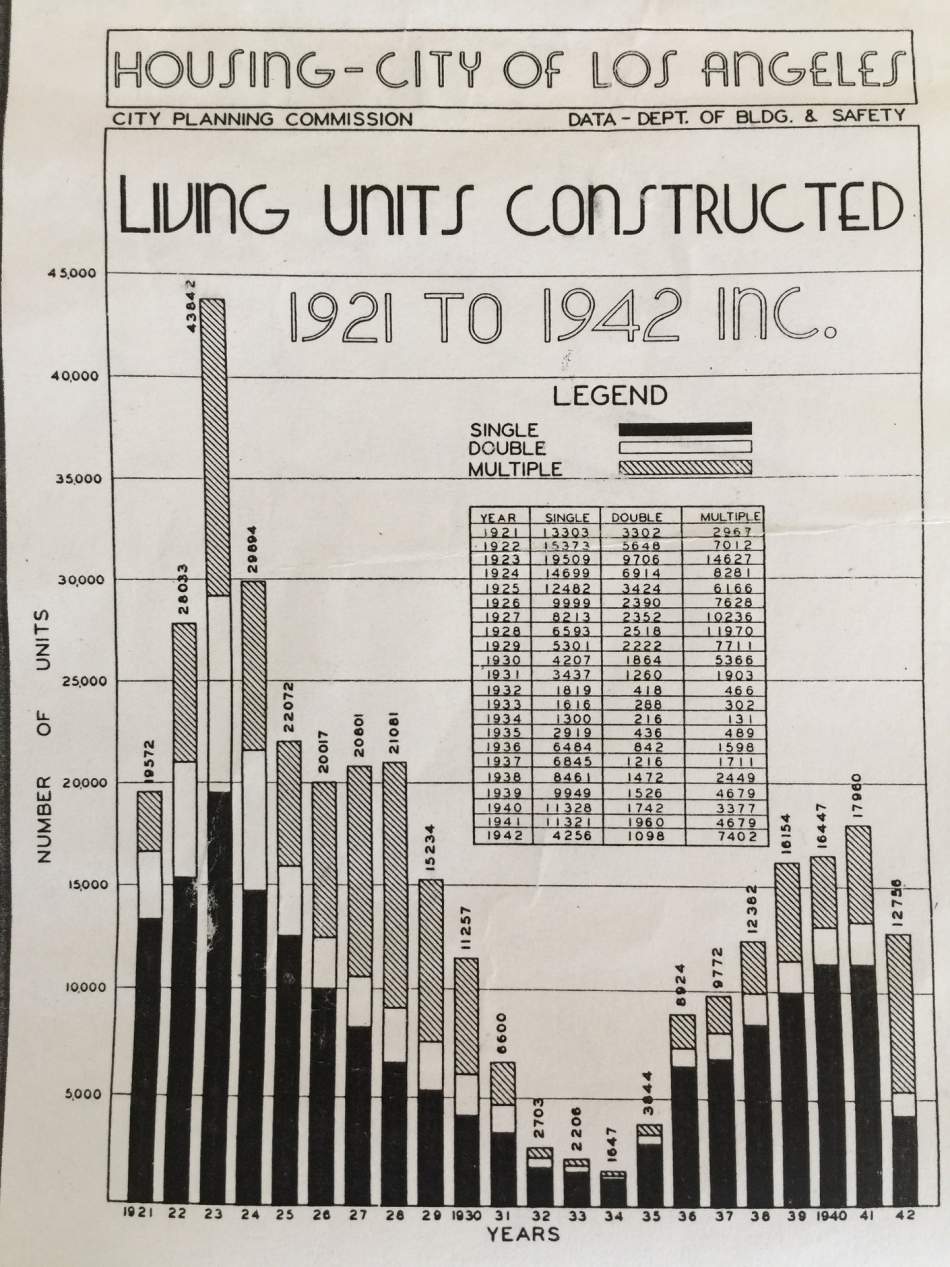

The reverberations of the region’s 1920s housing boom are still felt today. During this decade, the City of L.A. permitted somewhere between 210,722 and 232,000 new homes. (City figures show 210,000 between 1921 and 1930, another study by the Guarantee Building and Loan Association counted 232,000 from 1920-1929). These buildings are still a major source of the housing that we rely on to this day. Check out Omar Ureta’s interactive map of the age of buildings in L.A. County to see the age patterns of different neighborhoods. We tend to think of 20th century Los Angeles as being a city of single family detached homes, with apartments and renters becoming a majority relatively recently. But the 1920s housing boom was almost evenly split between one-unit homes and multi-unit buildings.

To put the housing growth numbers into perspective, Los Angeles today has approximately four times the population that it did in the midpoint of the 1920s. If we were building homes at the same rate as the 1920s, between 800,000 and 900,000 new homes would have been permitted in the past decade. In reality, just 84,764 new units were permitted between 2007 to 2016. Our comparatively anemic home construction - 1/10th that of the 1920s - is partly due to a lower rate of population growth and to a lack of empty land. But it is certainly worth noting what the policy framework was in the 1920s under which such a huge and diverse supply of homes was built.

The city passed a revised zoning code at the beginning of this period, in 1921. The code had five zones, including a precedent setting “A’ zone where only single family houses were allowed. The city of Berkeley had authorized single family only districts in 1916, but these needed to be requested by more than half of property owners in an area. Los Angeles’ A zone was among the first top-down mandatory single-family zones in the nation. According to Todd Gish’s dissertation “Building Los Angeles: Urban Housing in the Suburban Metropolis,” some planning commissioners supported creating two additional residential zones, one for small size apartments and courts, the other allowing larger buildings. But with zoning in its infancy, city attorneys worried about the legality of making too many distinctions; they were unsure if the single family zone would even stand up to challenge in court. Instead, L.A. enacted a “B” zone allowing any residential building. In both A and B zones, only residences were allowed- no mixing of commercial in with homes. In C, D, and E zones, however, residences could be included with commercial and sometimes industrial uses.

When the central portion of the city was zoned between 1921 and 1925 using this new code, 60 percent of zoned areas were put in the “B' category. This flexible residential zone allowed the hundreds of thousands of new homes constructed in this decade to be built in a mix of sizes and configurations on the same streets. Residents and speculative builders constructed single family structures, often with rear carriage houses/garages; duplexes; bungalow courts with 5 or 8 or 10 units on a standard sized lot; “accumulative architecture,” which were often small apartments attached to the rear or front of an existing house on the lot; two-story courtyard apartments; and taller brick apartments.

There were few explicit open space or parking requirements in the 1920s. Residential garages in the A zone were limited to a maximum of four vehicles. State housing law and local building codes required narrow courtyards in larger apartment buildings to allow light to reach each unit. To ensure access to rear buildings, Los Angeles passed a requirement in the early 1920s for a ten-foot-wide passageway to every unit. This passageway rule persisted for almost 100 years and ended up making it extremely difficult to build backyard homes on single family lots in L.A.

1930-1945

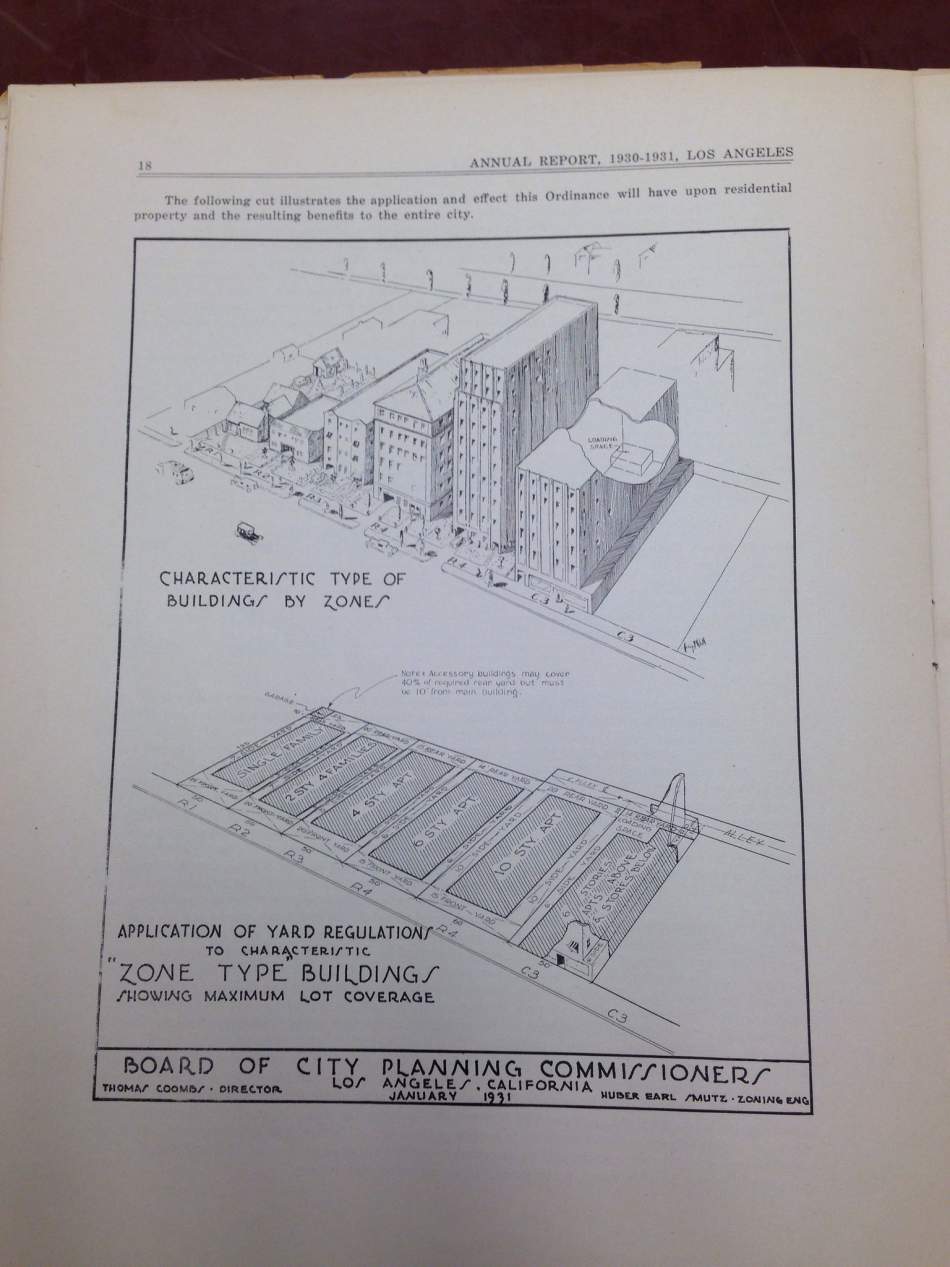

While the period between the start of the 1930s and World War II were a fertile period for the development of culture and industry in the Los Angeles region, and the city continued to grow, the depression and wartime building restrictions meant that home construction didn’t proceed quite as fast as during the 1920s. In 1930, the city revised its zoning code again to include eight zones. Four of these were residential. R1 allowed a single home, R2 allowed up to 4 units, R3 allowed residences up to 4 stories in height, and R4 allowed residences up to 13 stories/150 feet tall.

The code added two new requirements to multi-family residential zones: a two-car per unit parking maximum and an open space requirement limiting building coverage to a maximum of 60 percent of most lots. It is surprising to discover that L.A. had a parking maximum before it imposed parking minimums, but this didn’t last long. In 1934 and 1935, zoning rules were amended to require one parking space per unit in a garage on the lot of all multi-family residential properties. Also in 1934, L.A. passed a yard ordinance implementing recommendations from the Federal Housing Administration. This yard law required a minimum size front, rear and side yards for all new residences.

Parking minimums and open space/ yard requirements acted like a one-two punch to common bungalow court and apartments building designs.

Let’s consider some examples of pre-1930 residential buildings to see the impacts. One of the first buildings we stopped at on the Forbidden City walk was the building second from the left in this map. It is a two-story brick apartment building from 1926. It covers most of the lot. It was built in a sort-of dumbbell shape intended to ensure some light through side windows if adjacent structures were built up to or close to the lot line.

The intent of the yard ordinance was to forbid rows of attached buildings, like these three similar buildings built several blocks away in 1928.

In fact, LA produced infographics in the early 1930s to make the case for why a yard ordinance would lead to better residences and avoid the “ills” of row houses and blocks of attached apartments.

Andrew Whittemore, whose PhD thesis traced the history of LA zoning, has written about how mandatory yards and setbacks were encouraged in this period by the new Federal Housing Administration. The FHA’s carrot and stick was that it was more likely to underwrite mortgages in places with detached homes.

Parking minimums posed an even more serious challenge to existing building types. Some bungalows courts and courtyard apartments covered most of the lot, with interior open space that was not suited for conversion to parking. Other courts and apartments already had parking, often a row of garages or carports at the rear of the lot.

It is important to emphasize this point. People were building parking before the city mandated how many spaces were required, as vehicle ownership exploded in the 1920s. While the population doubled during the decade, vehicle registrations rose nearly sixfold (that figure is from L.A. County but vehicle growth in the city was similar). From 1920 to 1929, permits for 106,387 garages were issued by the City of Los Angeles. This is approximately half of the number of new homes permitted. Even assuming that many of these garages were single-car garages for single homes, a number of them would have been multiple car garages for L.A.’s small and medium sized apartments.

Garages are compatible with some multi-family residential buildings. Some building owners and residents clearly wanted on-site parking, but making parking garages mandatory was a different matter. On a standard dimensioned lot that was deeper than it was wide, it was hard to fit enough parking spaces in a row at the rear of the lot for all units, when there were more than say four-to-six dwellings. Many single story courts and most two-story courts, two-story courtyard apartments and two-to-four-story masonry apartments couldn’t fit one parking space per unit in their current configuration.

The new parking rules therefore forbid many common residential typologies and shifted how dwellings were designed. As Stefanos Polyzoides’ book Courtyard Housing in Los Angeles concludes: “Codes have changed radically since the 1920s, and they are the most evident factor for the abandonment of many desirable courtyard-housing features… The parking garages that are so discreetly handled in the originals through the use of a lovely tiled forecourt off of the street, a entrance from a small garage on the rear alley… have been replaced by a massive concrete garage below grade but open on the side to prevent the necessity for the forced ventilation that would otherwise be required.. Most, if not all, courts illustrated in this book are rendered obsolete with reference to parking.” He and his co-authors also identified stronger fire codes as influencing two story courtyard apartments. Requirements for more than one exit from upper floors led to post-World War II courtyard apartments having walkways ringing the interiors, rather than apartments opening directly onto a garden.

Less dense types of residential buildings were able to survive the introduction of mandatory parking. A common small apartment form that did work with the new yard and parking rules was a two story triplex or fourplex with a driveway on one side of the lot leading to garages in the rear.

When we considered some of the 1920s and 1930s building we saw along the route, Luke Klipp, President of the Los Feliz Neighborhood Council (but speaking in his individual capacity), mentioned that residents today appreciate these types of housing. Often when new developments are proposed in the area some residents ask why they don’t look more like bungalow courts and other small older structures that might ‘fit’ better in the neighborhood. There are many reasons, but one is that it is illegal to build these types of homes today.

1946- 1965

During and after World War II, Los Angeles experienced another wave of migration and growth. A housing crisis had arisen during the war due to federal restrictions on civilian construction, but once building picked up again, it remained at a high level throughout the late 1940s and all of the 1950s.

LA’s current zoning code was last substantially updated in 1946. There were five residential zones created at this time: R1 for a single unit, R2 for up to two units, and three multifamily zones. Previous zoning rules had indirectly limited the number of dwellings on a piece of property through height limits, setbacks and parking requirements. The 1946 code was the first to set density limits directly in these apartment zones by limiting the number of homes based on the size of the lot. In R3 zones, the minimum lot area per dwelling unit was 1,650 square feet, or a maximum of three units for a 5,000-square-foot lot. In R4 zones, the minimum lot area per unit was 800 square, a maximum of six units on a 5,000-square-foot lot. In R5 zones, the limit was 600 square feet, or eight units on a 5,000-square-foot lot.

Despite these new limits, apartment buildings remained an important part of L.A.’s housing supply. While the immediate post-war years were characterized by large scale subdivisions of single family homes, by 1957, the number of multi-family units permitted passed single family homes. Many new apartments were what we call ‘dingbats,’ low-rise, wood-frame apartments built with parking spaces tucked under the building, often with striking decorations on the front facade.

In his essay in the book Dingbat 2.0, Steven Treffers wrote that these apartments were integrally linked to the “standard family lot,” designed to put as many units as possible onto the site within the constraints of setbacks and parking rules. Parking minimums were increased in 1958, shortly after the dingbat boom started, to require 1.25 parking spaces for apartments with three or more habitable rooms (including kitchens) in buildings of six or more units. The amount of building frontage dedicated to driveways was also limited by this amendment, to address the look and safety of streets with long stretches where sidewalks disappeared. Treffers notes that “Architects would typically work backwards from these regulations, determining how many parking spaces could be provided based on the number of automobiles they needed to accommodate. In cases where 1.25 spaces per unit might be required, an architect might exclude a unit.. [for example] By building seven units instead of eight.. a builder would only provide eight parking spaces instead of ten.”

In 1964, parking requirements were increased further so that two-bedroom apartments needed 1.5 parking spaces each. Treffers reports that this increase “led to the end of the mass production of dingbat apartments by 1965.” After this date, apartment construction often meant combining two or more full lots for larger buildings with parking fully or partially underground, like this one on three lots.

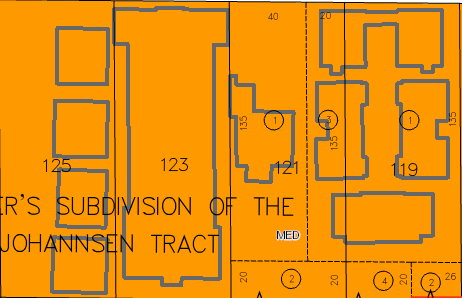

As an example for how zoning and parking influenced dingbat construction, consider this diagram of a 1962 dingbat on a 6,199-square-foot lot. The building has six units, 10 bedrooms (possibly 4 doubles and 2 singles), and six parking spots, all at the front of the building under or next to an overhang. The current zoning is R3, but it was R4 until the 1970s. R4 originally allowed one unit per 800 square feet, so the owner/developer could have constructed seven units. However, building seven units would have triggered the rule that 1.25 parking spaces were required for each unit - a total of eight parking spots. The building design would have needed to be changed to include a side driveway leading to some parking tucked under the side or rear of the building. Stopping at six units “saved” two parking spaces and the added cost of side parking. Note that If the same building had been built in 1965, it would have had to include eight parking spots as a six unit building.

The tour stopped at a couple of dingbats in Silver Lake. We had an interesting discussion about their merits, flaws and forbidding. Matt Dixon from Abundant Housing LA, a self-identified dingbat fan, spoke about how these apartments were often built by small contractors and sold to moderately wealthy individuals for the tax benefits of owning income-producing real estate. This ‘democratic,’ dispersed, standardized building model allowed more people to participate in development in L.A. More importantly, the apartments allowed many people to find homes in the city. Aaron Betsky, another contributor to Dingbat 2.0, had written in similar terms: “The dingbat functioned like the brownstones and tenements of New York, and in an earlier period, the apartment blocks of Europe, to house the millions that fed and made possible [L.A.’s urban growth].”

Other comments and questions acknowledged that dingbat design was more car-oriented (and parking-dominated) than we would like today, and that many of these buildings are now scheduled to be strengthened to improve seismic safety. Matt’s response to these points was that we don’t see 1958-style dingbats being built in 2017, but it would be nice if there were contemporary housing models that could be built in the ‘spirit of dingbats,’ that is, in a rapid and distributed manner to provide relatively affordable places to live.

In 1956, voters amended the City Charter to eliminate the 150 foot/13 story height limit imposed in 1911. In its place, four height districts were created, using floor area ratio rather than strict height limits to constrain building size. Our tour ended at a development that took advantage of a new era of taller buildings: the twin 14-story Los Feliz towers, which opened in 1966. In an ironic twist, the construction of these homes contributed to stricter height limits being imposed in many parts of the city. The first lines of a 1962 article in the L.A. Times on the towers said: “City planners are learning that proposals for high-rise apartment buildings are like sparks. They can touch off the most fiery sort of controversy.”

I call these individual buildings that sparked rule changes “backlash buildings” to distinguish them from other, less notorious forbidden structures. In the case of the Los Feliz towers, a backlash led to the City Council voting in 1963 to block construction by setting a six-story height limit on Los Feliz boulevard. The developers sued and were able to proceed because they had already received building permits. This controversy and similar concerns with other tall buildings led the city to add new, much lower height limits to the zoning system. The Los Feliz Towers are 196 feet tall. If the buildings were demolished and new homes built on the site, they would be limited to 30 feet and two stories by the 1XL height limit on the property.

1966 to Present

Through the late 1960s, Los Angeles had zoning without an overarching framework for applying it. To meet state requirements for a general plan, the city launched a public process to consider goals for LA and concepts for how it should grow and change. Los Angeles adopted a general plan in 1974 and launched a process to set zoning through 35 community plans. While the general plan identified areas of both growth and preservation, the politics of land use at the time were turning again development. Advocacy by homeowner groups and ecological concerns over population growth combined to influence the city to look to downzone many areas.

These downzonings were primarily carried out by changing zoning on properties. The city identified tens of thousands of acres that were zoned multi-family but where most of the homes were single family. Some of these sites were rezoned R1. Other neighborhoods, including the areas we walked through, were downzoned to lower-density multi-family zones.

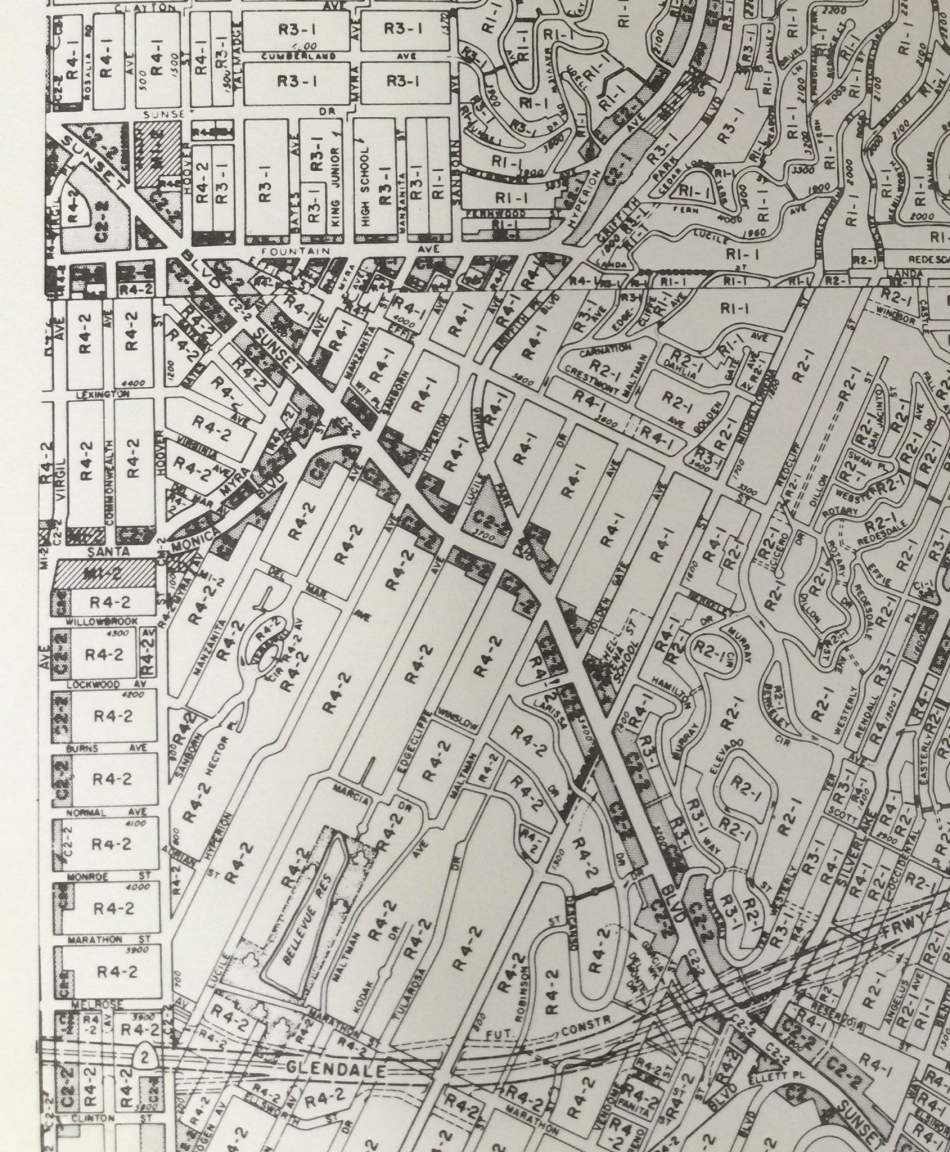

For example, in the early 1970s when the planning department began to prepare a community plan for Silver Lake and Echo Park, almost all properties surrounding Sunset Junction in Silver Lake were zoned R4-2. After the community plan was adopted and updated, most properties were rezoned RD 1.5-1VL, RD2-1VL or R3-VL. RD zones were created in 1964 as a tool to explicitly reduce residential density. This cut the number of units allowed on each site by half or fourfold and also reduced the allowable height of new buildings. Greg Morrow’s PhD dissertation showed how this type of downzoning, multiplied across the city, significantly reduced the number of homes (and people) allowed in Los Angeles.

Combined with parking requirements, setbacks, height limits and other rules, the number and type of buildings allowed on typical residential lots is much different today than it was in earlier decades. Consider these two buildings side by side near the Silver Lake - East Hollywood border.

One building was constructed in 1928, with 28 units (studios and one-bedroom units) and zero parking. The other, built in 2013, has a somewhat bigger lot, but only 11 (two-bedroom) units, and 20 parking spaces. To paraphrase the popular dog rates Twitter: they’re both good homes. It’s nice to have a diversity of dwelling types and sizes. But should it be illegal today to construct an apartment with more units and less parking?

Another example we noted on the walk was a four-unit small lot subdivision on a 8,000-square-foot lot. Four homes is the maximum that can be built on this property under its current RD 1.5 zoning. Eight units could have been built there under the previous R4 zoning (if space could be found for parking).

Some people don’t like that small lot subdivisions, legalized by the city in 2005, are being built in LA. The City is considering amending the ordinance “to ensure small lot projects will be more compatible with the existing neighborhood context and zoning” .. with rule changes to “limit the buildable area of the lot [and] require greater setbacks.” The amendment would also legalize subdivision of existing bungalow court with too little parking or too high density. If any new units are added to a bungalow court, or if anyone tries to build a new small lot subdivision in a court orientation, they have to comply with parking rules, setbacks and other regulations.

Will new small lot subdivisions go the way of bungalow courts or dingbats? Probably not. These new rules will reduce the number of homes that can be built on some properties, and, in some cases, they may make in economically infeasible for small lots to be done at all. Yet it does seem like the forbidden city history is repeating itself to some extent. A building type becomes popular, and rather than welcome the new homes, the city is seeking to restrict them.

We need a new boom

As related above, the 1920s in LA were a period of extensive growth and change. Land speculation led to wildcat subdivision and buying and selling of property. Demand was high thanks to rapid population growth. Many newcomers were relatively affluent. Tens of thousands of homes were constructed with hopes of renting them to tourists or part time Angelenos who wintered in Southern California. Smaller buildings were regularly demolished or moved from one site to another. Given contemporary concerns about similar trends (speculative investment, AirBnBs, absentee owners, out-of-scale development, demolitions, etc.), one might assume that 1920s L.A. must have been in the midst of a housing crisis. One would be wrong. In November 1928, a rental agency surveyed average rents in eight parts of Los Angeles city and adjacent smaller towns, looking at costs of five-room single family apartments, five-room flats, single-bedroom apartments, duplexes and bungalow courts. They reported a “lower average for all classes of housing than in virtually any other large city in the United States.” Rents in L.A. city for apartments ranged from $30 to $60 monthly. This was 25 percent to 30 percent less than in comparable big cities.

How could that be? The 1920s housing boom, for all its boosterism, speculation and relatively unplanned construction, allowed supply to rise to address the growing demand. Rents aren’t the only factor in the housing equation of course. Residents’ income is also important. Since L.A. city today has both high housing costs and many low-income residents, the rent burden is more severe in L.A. than in some cities where homes are even more expensive. But the fact remains that when it was legal to build more homes in the city, housing costs were lower.

The past is just that, and we can't simply return to the way things once were. We won’t (and wouldn’t want to) copy any past housing boom. When thinking about how to address L.A.’s housing crisis, we should, however, explore what it would take to allow a new one.

Allow diverse, low-rise residences almost everywhere

One lesson we can learn from past housing construction is that we should zone LA so that a range of single unit homes or low-rise apartments can be built on most standard sized residential lots. The old “B” zone from the 1920s or R3 zone from the 1930s would be good models. Small multi-family homes of between 4-to-10 units are among the cheapest dwellings to construct and should therefore be encouraged. This will allow more naturally-occurring, unsubsidized, relatively-affordable housing.

Normalize home building

Recall how Charles Greene’s criticized bungalow courts in 1915 for being speculatively developed, too standardized and too dense. These three arguments against more and different homes have been repeated in L.A. for a century. As they increasingly prevailed in recent decades, the city became a more expensive place to live.

We need to flip the critique and recognize that building standardized homes for profit, in arrangements that are somewhat more dense than existing dwelling patterns, has been and will probably continue to be the key way that we will provide enough homes for L.A.’s diverse population. The City will also need to do a better job subsidizing social housing, protecting tenant rights and encouraging more efficient construction methods. But in my view, to have a chance at solving our housing crisis, we should treat land development more like a normal business. This means setting rules to get good quality homes and then making it easy for a range of people, businesses and organizations to build them. Our current planning system, which treats home building as a bizarre activity that requires a multi-year ritualistic process of meetings, delays, extractions and litigation, should be re-focused on high level goals for the city.

End parking minimums

It’s time to eliminate mandatory parking minimums in Los Angeles. Our 80 year experience with these requirements can only be judged a failure based on its impacts on housing, mobility and traffic. Two L.A. Walks steering committee members who joined us on the forbidden city walk, architect Daveed Kapoor and John Mimms, who works in affordable housing, shared how parking requirements, rather than human needs, too often drive the design and cost calculations of new housing. As referenced above, plenty of parking was built in L.A. before mandatory parking minimums. Plenty will still be built if we eliminate these parking mandates. By getting rid of them, what we can accomplish is to legalize better designed homes with less parking for people who can’t afford a car or want to be car-free or car-light.

Test new rules before imposing them

Another lesson from L.A.’s forbidden city is that we should think more carefully about standards we apply to residential development. They can eliminate building types that provide a large share of homes. With the exception of urgent life and safety standards or other important building code updates, I would suggest that L.A. should test out proposed rules on real buildings before imposing them on all new construction. For example, if the city thinks that small lot subdivisions need bigger setbacks, pick a couple of properties that the city owns and run a design competition for it based on the old and new rules. Lease the lots to developers and have the winning entries built and actually lived in for a couple of years. Then survey the residents and their neighbors to see what lessons can be taken from their experiences. If the new rules lead to superior homes and do not reduce the housing supply significantly, maybe they are worth applying citywide or in certain contexts.

Preserve the future

The forbidden city walk was an opportunity to honor older buildings and to learn when and how they were banned. Tackling our housing crisis, allowing the city to evolve, and saving parts of our past will require a balanced approach to historic preservation. Individual significant buildings can be landmarked. Many older apartments are still an important part of L.A.’s housing, and they can be adapted and updated to meet present needs. For example, we stopped at one 1920s brick apartment building where a parking lot had been added underneath the structure. It also had its parapet wall stabilized in 1968 (to prevent this small rooftop extension from falling during an earthquake), fire safety enhancements in 1984 and a retrofit of the building’s unreinforced masonry structure in 1988.

I think we also need to expand our vision of preservation to figure out how to better preserve the future. In other words, in addition to working against the demolition of existing bungalow courts, how can we ensure that the contemporary equivalents of these popular vernacular homes can be built today? When we were planning to launch LAplus, Ava Bromberg, one of our co-founders, suggested that an important goal should be to have more ‘generative’ rules for L.A.’s built environment. Given L.A.’s history as a place of reinvention, one of the best way we can honor Los Angeles’ past is to remove barriers to its future.

Mark Vallianatos is the Director of LAplus la-plus.org , a co-founder and steering committee member of Abundant Housing LA, and a member of the Re:code LA zoning advisory committee. The opinions expressed in this piece are his personal views.