From the editor: “L.A. Urbanized” is a series of articles exploring why Los Angeles is currently in the midst of an urban revolution and what it means for the city’s future. It documents the evolving development landscape of the region over the past few decades, identifies what key events brought about its urbanist turn, and considers what the impact of this transformation will be. Urbanize LA will publish one chapter of the 9-part series each Monday from April 2 through May 28.

Previously:

From LA’s genesis as a city, its shape has been engineered to an unusual degree by the workings of politics and special interest groups. The city has been radically transformed over the course of its history by people who conceived of a grand vision for the place, and had the power to transform that vision into reality. For much of LA’s history, that sense of vision for the region centered around boundless growth, with the intention of delivering a certain conception of the American Dream to an endless stream of new arrivals.

At a certain point during the 1970s and ‘80s, however, this set of ideals was largely turned on its head in the public discourse, and the new aim of much public policy in the region was directed toward the preservation of existing ways of life and mitigation against the ills of overgrowth. This turn against growth did not, however, put a complete stop to it. Rather, we shall see how this sort of political movement had the unintended effect of turning growth inward, toward the urban core of the region, setting the stage for the leap from the sprawling 2.0 model to the hybridized 3.0 model that was to come.

“Boosterism” and the Creation of Southern California

For much of the twentieth century, LA was synonymous with high-growth, sprawling development. Indeed, the city as it is known today was built by a tireless ‘growth machine’, as the sociologist Harvey Molotch puts it. The ‘growth machine’, an oversimplified abstraction of course but a useful one, refers to the coalition of “‘place entrepreneurs’ such as land speculators, bankers, newspaper publishers, politicians, and public utilities with a stake in the economic growth of a particular economic area.” The growth machine wielded preponderant clout in Los Angeles from the late nineteenth century roughly through the 1980s, engaging in a thorough form of “boosterism” — the promotion of a newly developing region for the purposes of promoting investment and migration to that region.

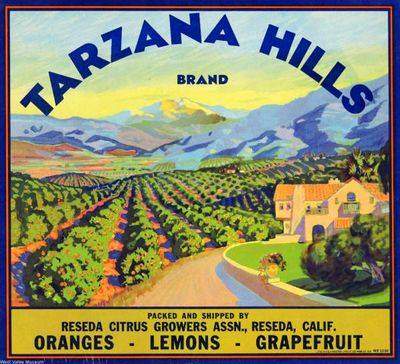

Indeed, Oxford historian James Belich describes Southern California in the early twentieth century as “a place where boosterism became almost a second religion”. In the early years of its big boom, Los Angeles was a place with few exportable products available. Some citrus fruits were produced there for export, but this product was nowhere near sufficient to power the growth of a major metropolis. Los Angeles also lacked sufficient drinking water or a natural harbor. It did have idyllic weather and abundant land, however, and its boosters exploited those assets for all they were worth. LA boosters were able to convert thousands of tourists and vacationers into settlers, who often then found employment on public works, the biggest industry available there at the time. Investment poured into Los Angeles and built modern residential and commercial space on a mass scale, even though at this time “the region’s most important export was probably letters back east, [...] which joined the formal booster literature in sucking in people and money.”

LA boosterism led to mass infrastructure projects that brought LA drinking water and a port. The city had insufficient water for future growth, so LA Water Department head William Mulholland schemed and succeeded in gaining access to water from the Owens Valley, hundreds of miles away (a story made infamous by its depiction in the movie Chinatown). The region had no natural harbor, so the city elites built breakwaters and wharfs on artificial islands to create one. The city had insufficient people, so newspaper publishers with real estate interests boosted the city’s image to cold Midwesterners with the aim of attracting them to resettle.

The result of this frenzied speculation, however, was a desperate need for solid long-run industries. As Belich describes, “practically every means of using the land was tried at least once in southern California, including ostrich farming and the cultivation of silk, rice, and rubber trees.” It was only by chance that in the 1920s oil and film production turned out to be sustainable export industries from Los Angeles (the technology to support these industries did not even exist at the start of LA’s boom). Virtually no early boosters had envisioned either ultimately effective export industry as having a future in Los Angeles, but their efforts in building up LA’s physical building stock and infrastructure allowed for these industries to function effectively in the long-run.

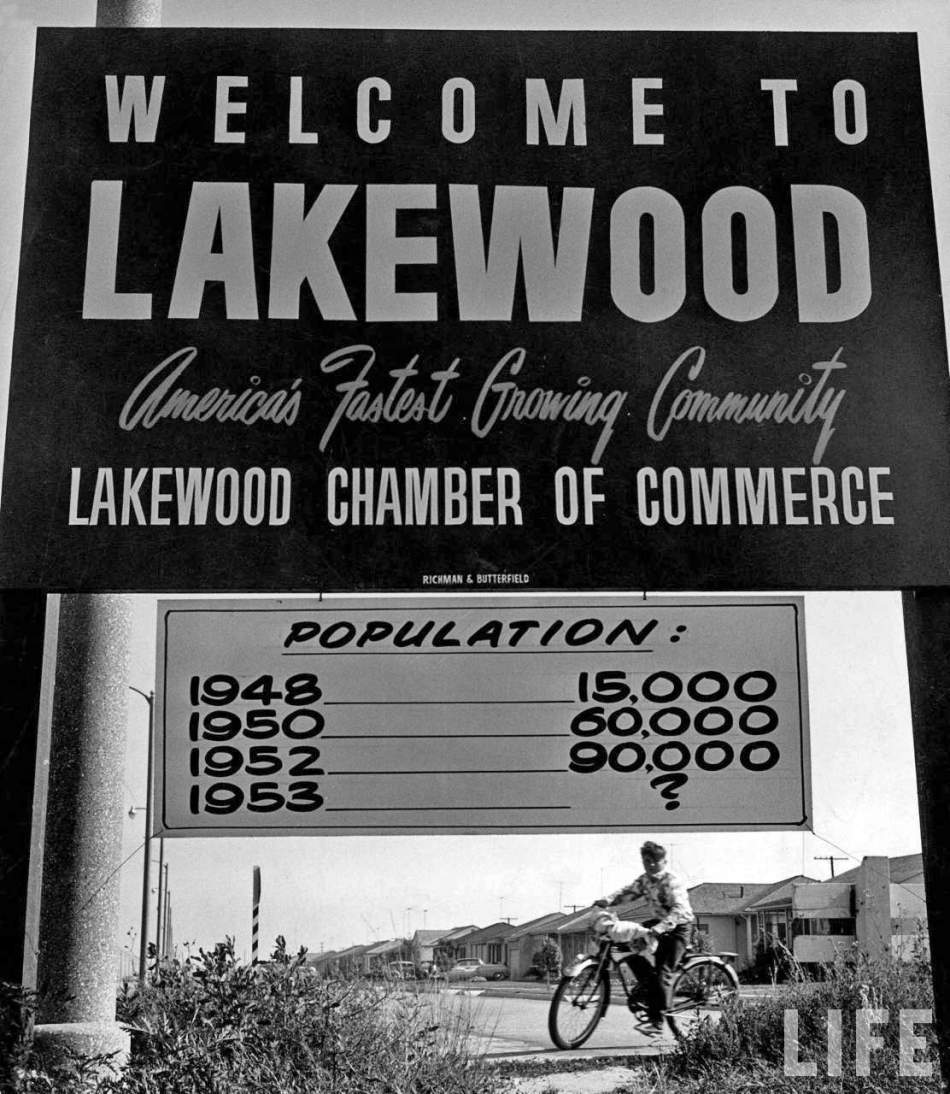

This formula of boosting and channeling investment to ultimately profitable new industries actually worked well for a long period of time. Over the course of the century, and especially in the decades following from WWII, growth in LA was explosive, with the region’s population rocketing from about 3.5 million people in 1945 to about 18.5 million people today, and the metropolitan economy expanding to become the third largest in the world (behind only Tokyo and New York). Through the 1980s, the growth of LA’s built environment kept pace with its population and economic growth, but when political currents changed directions around that time, the shape and the character of the city was changed permanently.

The Rapid Growth of LA 2.0

All of the new people coming to LA needed places to live and work. Many cities that have experienced such rapid growth have responded by building up, to fit more people within limited space. But generally LA’s ‘growth machine’ provided this space by building out rather than up, as a result of the particular place and time in which LA experienced its most rapid growth. Most American and European big cities experienced their major growth spurt during a time when cars were not in mass-usage, so cities needed to be built in such a way that they could transport people by streetcar and commuter rail. It was also common in times before advanced industrial technologies for major cities to be built within some major bay, as a means of giving trading ships natural harbor. As a result many traditional cities (including New York, San Francisco, Boston, and more) were constrained within an island or peninsula that limited horizontal growth. The natural response to these constraints is the sort of dense, tall style of development that is typically considered ‘urban’.

But Los Angeles had few natural barriers to growth that the technology of the time could not deal with, and the city experienced its growth spurt during an era when car ownership was widely available, and thus cars could function as the primary transportation means around which to build a city. This auto-oriented arrangement functioned well for a period of time. Before the advent of mass car ownership, urban growth was constrained by the necessity of commuters living near rail lines. Rail lines are expensive to build and operate, and they need high ridership in order to justify their costs, so high densities of residences and businesses would need to cluster in close proximity to rail lines under the previous model. Outward urban expansion was difficult under this model, because the fixed costs of adding new rail lines and services was rather expensive.

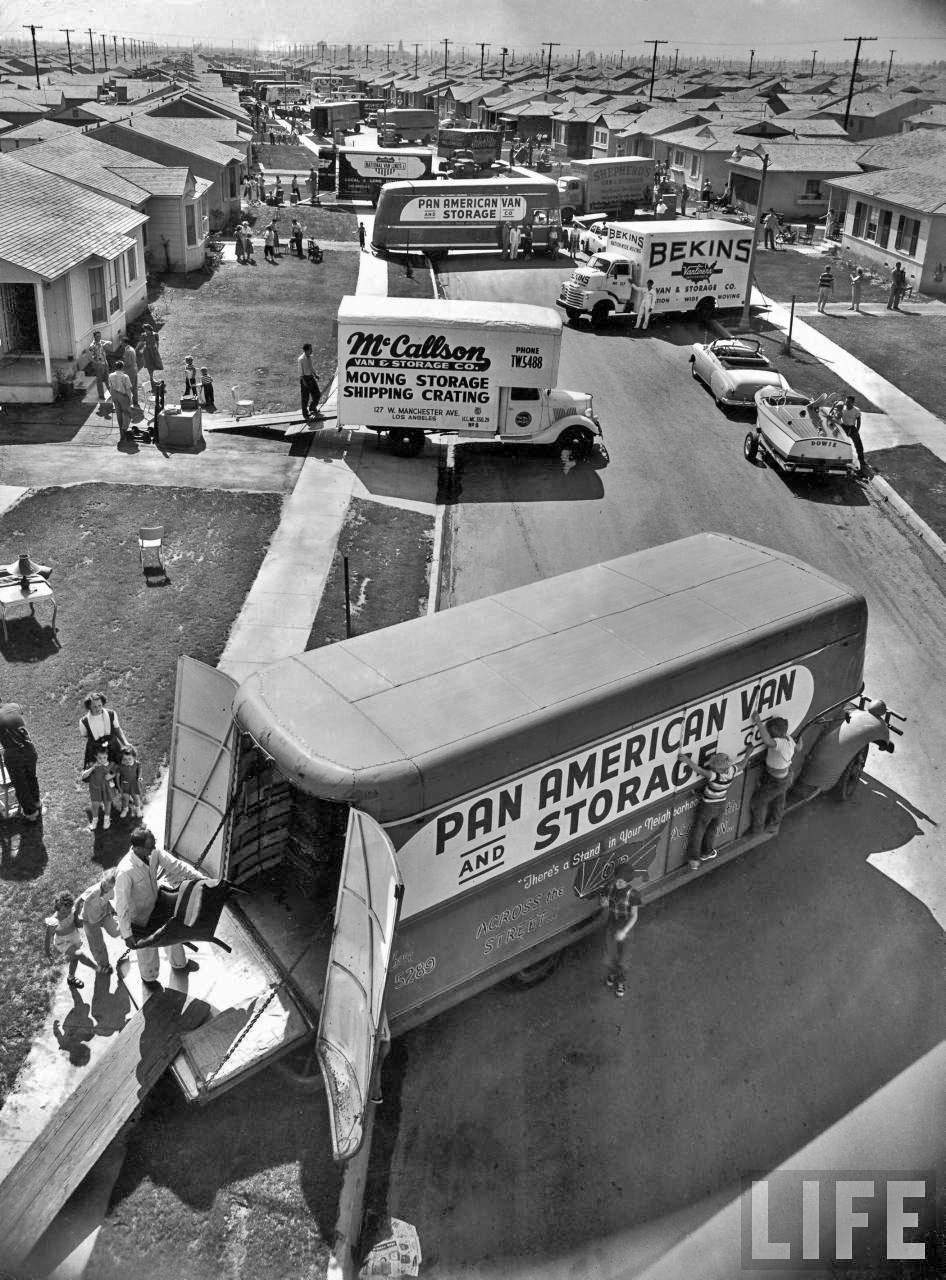

But in a world with mass car ownership, urban expansion became almost as simple as adding pavement. Land that was formerly used for farming on the edge of the city could be quickly and profitably developed into suburban subdivisions. The San Fernando Valley, to the northwest of LA’s city center, for example, served as the archetypical model for this style of development. The vast farming flatlands of The Valley, as this region is commonly called, were developed as the ultimate ‘bedroom community’ suburbs for former GIs returning from WWII and settling down to create their families. This sort of underutilized land was so abundant in mid-century Southern California that great numbers of people who could never dream of owning their own home elsewhere in the country suddenly could find their own visions of paradise out in California. Housing remained affordable for a long time across the region, because as the economy grew and new people came to the city, there remained new land available to develop, seemingly ad infinitum.

But ultimately this model, the post-war LA 2.0 model, ran up against its own constraints once this ‘virgin land’ began to run out. In the functioning model, housing remained affordable because supply continued to expand via outward development together with the growth of demand and the economy, and transit about the city was relatively easy because the number of people was small enough such that the roads and freeways were seldom at capacity. But once the city ‘filled up’ and outward expansion could not keep pace with population and economic growth, which took place generally in the 1970s and ‘80s, these assets were flipped on their heads. Even with the increasing construction of multi-family residential developments, the housing supply began to stagnate as compared to surging demand, significantly increasing the cost of housing and in so doing destroying the institution of home-ownership for most people in LA. And with all of the new people on the same, now limited, number of roads, traffic congestion of famous proportions eliminated the easy mobility that was one of LA 2.0’s strongest advantages.

The Development of Anti-Development Politics

Not coincidentally, it was around this same time period that political opposition to new development became mainstream in Los Angeles. Opposition to development was not new to the city, but it had certainly been a minority opinion during the ‘anything goes’ years dominated by the ‘growth machine’ leading up to the 1970s. The first major movements against growth were centered on residential hillsides in the 1940s and ‘50s. Many of the denizens of these zones were there specifically seeking peace and isolation, and so they were naturally opposed to the introduction of lots of new neighbors. During this period of time, additionally, much of the earth moving technology was developed only a little bit earlier during WWII, and it was not really perfected yet, so opponents saw a greater risk of landslides than we might expect today from such activity. But this sort of opposition movement was fairly limited, until we reach the 1960s and ‘70s. During that period of time, new opponents to development emerged, viewing limits to development as an ecological imperative. This group successfully lobbied LA Mayor Tom Bradley to downzone significant swathes of the city, disallowing higher intensity levels of development.

The real rejection of the growth model as a whole was not to come until the ‘70s and ‘80s though. It was during that time when most middle-class people in LA came to adopt the ‘slow growth’ platform on the grounds that development would add traffic and disturb the low-density character of their neighborhoods — objections so common today as to be considered the ‘generic’ ones by land use professionals. These concerns are at times valid. But many commentators, not least the perceptive if often polemical urban critic Mike Davis, have argued that “although many of the movement's concerns about declining environmental quality, traffic and density were entirely legitimate, 'slow growth' also had ugly racial and ethnic overtones of an Anglo gerontocracy selfishly defending its privileges against the job and housing needs of young Latino and Asian populations.” Indeed, one of the driving forces behind the ‘slow growth’ movements can be interpreted as an ‘unholy alliance’ between a left-wing opposition to development on anti-capitalistic and anti-gentrification grounds and a right-wing opposition on anti-integration grounds. Regardless of their motivations, the powerful anti-growth forces spawned in the ‘70s and ‘80s, together with a series of 1990s setbacks for the city, to be elaborated upon in a subsequent installment, broke the LA growth machine. The ‘anything goes’ growth model of the past had been sent to the history books, and as this dominant anti-growth sentiment cemented itself in public policy over the past few decades, the unintended consequences have been profound.

Low-Growth Politics; High-Growth Rents

While most major cities face excess demand for housing and some form of political opposition to more provision of it, political arrangements peculiar to Greater LA in particular exacerbate this challenge. Los Angeles County (itself one of five counties in the Greater Los Angeles region) is home to no fewer than 88 different municipalities, each of which has its own particular building codes, bureaucratic processes, and specialized anti-development groups. Some of Greater LA’s most desirable neighborhoods, such as Santa Monica or Beverly Hills, are legally their own municipalities, and these city governments tend to be even more opposed to further development and regional integration than is the norm for the region. Even certain districts within the City of Los Angeles proper have their own community development rules quite hostile to further construction.

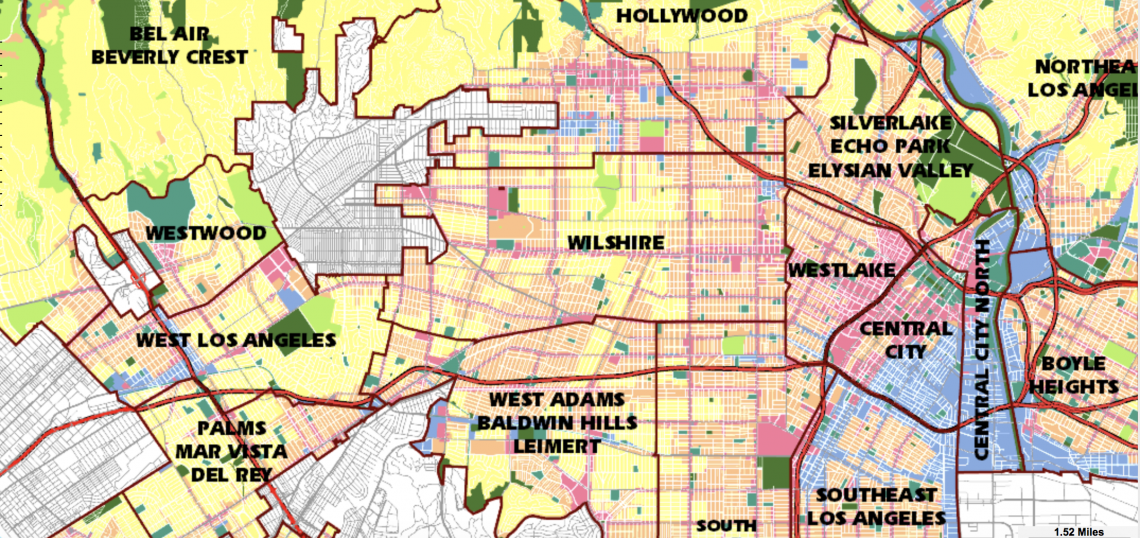

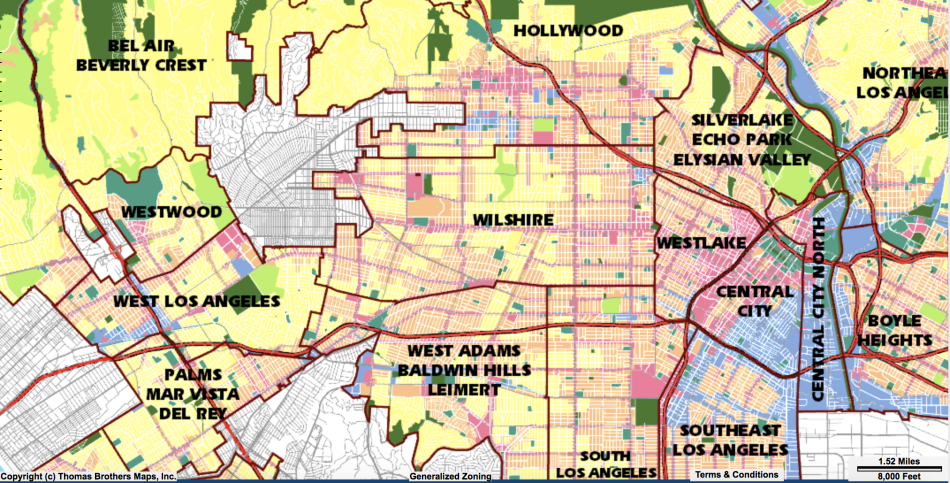

The late twentieth century economic and cultural heart of the Los Angeles area generally ran in a linear fashion from Downtown westward through the neighborhoods Hollywood, West Hollywood/Mid-Wilshire, Beverly Hills, Century City, West LA, and to Santa Monica and the other oceanfront neighborhoods – a concept outlined by Samuel Krueger through a well-publicized USC graduate thesis. Almost all of those locales were ardently opposed to mass development, and many of them had the independent political power to turn that anti-development sentiment into policy.

Politically active residents of LA’s most desirable neighborhoods were often incentivized to oppose development, and they had the tools with which to block it. From an ends perspective, many LA-area homeowners — who are more likely to be politically active than renters — are incentivized to oppose new development in that the short supply of housing bolsters the value of their homes. From a means perspective, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), passed in 1970, makes it very easy to sue developers to block construction projects. The city zoning code, in which 78% of the city’s residential land is zoned for single-family homes, has changed little since the 1940s, when Los Angeles was relatively provincial. Surely it is important for developers to be held accountable to citizens, and low-density living environments do have their advantages, but for whatever advantages they offer, one of the trade-offs is a constrained and expensive housing market.

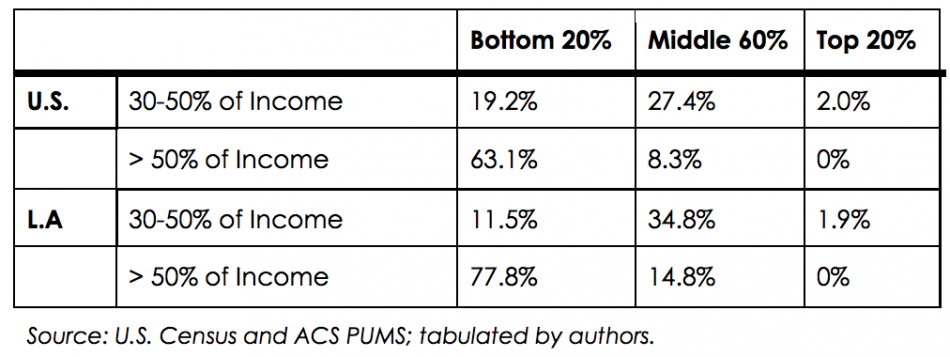

The result of this unusually strong opposition to dense development is that Los Angeles is a remarkably expensive housing market due to limited supply. Indeed, a recent study from the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate named the Los Angeles area as the least affordable housing market in the United States, when rents are considered against income. Roughly a third of Los Angeles area denizens are paying over half of their income on housing costs alone. With rents so high, surely market pressures are incentivizing the development of additional housing units within the LA region, and an expanded housing stock would benefit many LA denizens by lowering the amount of money they spend on housing. But across Los Angeles, housing development is simply not keeping pace with demand as a result of localized opposition.

The Funneling of Growth to the Urban Core

Downtown Los Angeles, however, was less the setting of opposition to development than are any of the other locations within LA’s economic core. At the outset of its redevelopment, DTLA was one of those areas where barriers to development were weaker. In contrast to the people of Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, etc., Downtown’s local population was mostly impoverished, disorganized, politically weak, and few in number, so they were less capable of putting up political resistance to development in a fashion similar to those more westerly Angelenos. Further, much of the development Downtown would be replacing parking lots, rather than current housing or historic buildings, so the specter of old buildings being destroyed or low-income tenants being evicted was less directly present. The DTLA of the ‘80s and ‘90s inspired relatively few people to defend its existing form. Finally, Downtown was governed solely by the City of Los Angeles, which was relatively pro-growth as a means of addressing the affordability crisis, and the city government actually did quite a bit within its power to encourage high-density growth Downtown. A similar pattern, though to a less exaggerated degree, was present in other urban core neighborhoods such as Koreatown and Hollywood, all of which are being transformed into the “Fifth Ecology” we speak of in this paper.

The concept of how opposition to development in much of the region has funneled growth to the urban core can be illustrated by way of example. Imagine a developer has a certain amount of capital to deploy in the Los Angeles region. He/she may want to build an apartment complex in the West Side municipality of Santa Monica, where the balmy beach weather, proximity to high-paying jobs, and low crime would allow the complex to command high rents and be very profitable. But the city government of Santa Monica is very opposed to this developer’s proposed project, and will not grant it approval. In fact, this structure very much struggles to gain approval in any of the high-rent neighborhoods on the traditionally desirable West Side of Los Angeles, in which opposition to new development is very strong. This developer would likely achieve lower returns by building in a lower-rent neighborhood further east (more in the urban core, closer to DTLA), but those neighborhoods are the only places where he/she can secure government approval, and the pricing for housing across the region is high enough such that the project is still reasonably profitable, so the developer chooses to build closer to the urban core.

The aggregation of these types of individual private business decisions, repeatedly made in response to fixed political realities, has been one of the primary driving forces shaping growth patterns across Los Angeles over the past few decades. Anti-development actions in Los Angeles have been akin to keeping steam in a boiling pot; where the pressure keeping development contained was weakest, in DTLA (and a few other proximate neighborhoods), development was most likely to explode onto the scene.

Previous chapter: Introduction

Jason Lopata works as a land use consultant with Craig Lawson & Co., LLC, helping real estate development projects in LA navigate the city approvals process. Jason previously spent time on the Business Team of LA Mayor Eric Garcetti. He also writes articles on globalization and urban development for Stratfor, the geopolitical analysis website. Jason received his bachelor’s degree from Stanford University and completed programs of study at the University of Oxford and at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. While at Stanford, he founded and led the student real estate organization, and authored his senior thesis on Los Angeles development over the past 30 years.