Editor’s Note: “Neighborhood in Focus” articles take a deep dive into a particular Los Angeles area neighborhood. They explore its origins, its history, and recent transformations that have made it a center of urban transformation.

Hollywood is a neighborhood with a name and reputation that precedes itself. This area played a critical role in the development of the entertainment industry, such that today when people say “Hollywood”, they’re usually referring to the industry rather than to any defined geographic space.

But the term “Hollywood” carries even more weight than that. Though the film industry had its roots in the neighborhood, as Los Angeles suburbanized in the years following from World War II, so too did the entertainment industry. Its center of gravity split, migrating westward toward the Westside, and northward toward the East Valley and Burbank. When Hollywood left Hollywood, the neighborhood fell into a state of disinvestment and disrepair. As such, by the time of the 1980s and ‘90s, the word “Hollywood” had assumed a new connotation within Los Angeles: one of dereliction and decay.

Around the turn of the millennium, Hollywood began to rebound as a neighborhood. In many respects, this turnaround was the product of the same cultural changes and land use policies that have resulted in the growth of urban areas across the country. Hollywood’s story is unique, however, in that it represents an industry returning to its roots. This is not out of a sense of sentimentality, but rather because Hollywood the neighborhood is an economically efficient home for Hollywood the industry. By no coincidence, the neighborhood is located in the center of the two areas (the Westside and East Valley) into which the industry sprawled decades ago.

As Hollywood has experienced its resurgence, its sub-neighborhoods, each one centered on its own major commercial boulevard, have grown in their own ways. Hollywood Boulevard remains the primary tourist draw in the area, and its character is very much shaped by that appeal.

Moving a bit south, the area along Sunset Boulevard and Selma Avenue are developing their own distinct character as a major employment center, with Netflix and other new media companies, and as a lifestyle center, with the Dream Hotel and other emerging attractions. Proponents of this area are making an effort to brand it as the “Hollywood Vinyl District”, given its historical connections to music industry production, and the modern appeal of that medium. For the purposes of identification in this article, I’ve utilized this name to refer to this distinct area, though it remains to be determined what the area will be referred to in common usage as it matures.

Moving further south, and west, we arrive at the Hollywood Media District, centered on Santa Monica Boulevard in the vicinity of Highland Avenue and La Brea Avenue. This neighborhood, which was traditionally an industrial back-of-house for the entertainment industry, is undergoing its own transformation a la the DTLA Arts District: industrial facilities giving way to artist lofts and galleries, which themselves quickly give way to high end office and residential.

As these districts solidify their identities over the years to come, we may need to think in terms of several Hollywood neighborhoods, rather than one monolithic whole.

Old Hollywood

Hollywood was incorporated as its own municipality in 1903. Ironically, many of its early organizers envisioned Hollywood as a pastoral temperance colony. Yet that initial vision did not last long. By the 1910s, Hollywood had been annexed by the City of Los Angeles, and it was quickly emerging as the home of the country’s motion picture industry – one which had hardly existed just a decade earlier when Hollywood was founded.

Many movie studios originated in the New York City area. But their activities were constantly disrupted by law enforcement, because they were in violation of strict patent protections owned by Thomas Edison, based in nearby New Jersey. Filmmakers found that in those days, Mr. Edison’s patents were not so stringently protected in a frontier town across the country like Los Angeles, making it a more hospitable home to set up shop. Moreover, LA’s climate provided more filming days per year, its diverse topography allowed it to stand in for many film settings, and its abundant space permitted the construction of larger film studios. Downtown LA and its environs were already too densely developed to locate studios in by the 1910s, but Hollywood at that time was spacious enough to accommodate them.

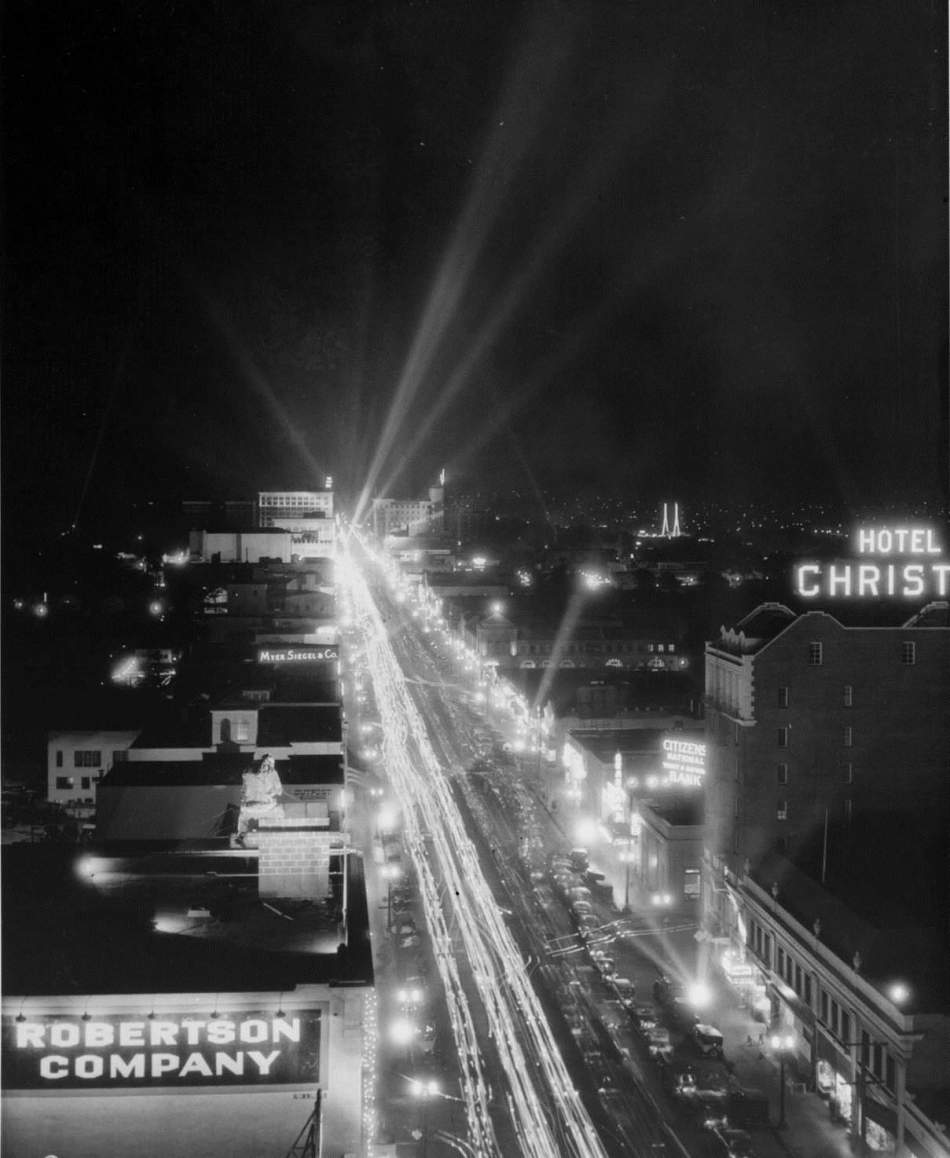

Over the ensuing decades, the film industry in Hollywood boomed. Its product matured from short sketches, to silent films, to talkies, to the effects-laden feature films with which we are familiar today. The neighborhood of Hollywood boomed alongside its namesake industry, such that by the 1920s Hollywood was home to elegant hotels, resplendent theaters, and movie star mansions.

By the time of the late 1920s, Hollywood, which has always to some degree maintained an identity separate from that of its wider region, began to envision a future for itself where it functioned as its own metropolitan commercial core, capable of competing with Downtown LA. Hollywood pursued what it called its “Five-Finger Plan”, promoting high-rise development along Hollywood Boulevard and five streets that intersect with it. This plan achieved limited success in its time, but its intent was never fully realized due to the Great Depression in the 1930s and subsequent events. (However, the high-rise densification of Hollywood today can in some respects be thought of as the eventual fulfillment of the Five-Finger Plan, nearly a century later.)

Such plans for Hollywood’s future greatness were put on hold in the ‘30s, ‘40s, and beyond as a result of the Great Depression, World War II, and most critically, the suburbanization of the film industry and the city more broadly. In the decades following WWII, which ended in 1945, most Angelenos with the means to do so decamped from their urban neighborhoods to the suburbs. In the case of urban Hollywood, the studios followed their executives and employees to their new suburban homes. The movement was gradual, meaning that suburban studios needed some degree of proximity to the original industry cluster in Hollywood. As such, the suburban neighborhoods to which Hollywood (the industry) decamped were those on the West Side and East Valley closest to Hollywood (the neighborhood).

Having lost many of its wealthier residents and much of its economic engine, Hollywood the neighborhood largely fell into disrepair. Grime and crime supplanted glitz and glamor as the primary image of the neighborhood in the public imagination. The mythic allure of the Hollywood Walk of Fame was recreated at theme parks such as Universal Studios and California Adventure, but for decades tourists visiting the actual destination were in for an unpleasant surprise.

Critically, however, unlike Downtown LA Hollywood never fully lost its residential population. The people living in Hollywood in the late 20th century had less money than their early 20th century counterparts, but their continued presence maintained a 24/7 vibrancy in that neighborhood, whereas at its low point DTLA had very few residents. This distinction means that Hollywood had a more active set of stakeholders than DTLA did during its resurgence, affecting the conversation surrounding redevelopment there in a more controversial fashion.

Hollywood Yesterday

The story of Hollywood’s turnaround bears some similarity to that of DTLA and other urban neighborhoods in the city. Throughout most of the 20th century, LA’s population and economy grew, and the city accommodated that growth by sprawling outward. By the time of the late ‘80s and ‘90s, however, it seemed that the city might have been approaching the limits of that outward growth, given unmanageable commute times and geographic constraints. At the same time, the city downzoned much of its land through measures such as Proposition U in 1986 and informally through citizen activism.

The ill effects of this supply constraint were not immediately evident, however, because these events occurred around the time when LA’s economy took a big hit with the shrinking of the aerospace industry at the end of the Cold War in 1991. The ensuing economic contraction slowed demand growth, and together with a relative oversupply of housing and office space developed in the 1980s, these limits to supply growth were not immediately felt in the market.

Once economic growth returned to Los Angeles in the mid and late 1990s, however, the only places where developers could add meaningful new supply were those urban neighborhoods, such as Hollywood, where opposition to growth was less potent than it was in the region’s higher income locales. Like steam in a boiling pot, development escaped through the openings in its lid: neighborhoods such as Hollywood, Koreatown, and Downtown LA.

Developers operating in Hollywood in the 1990s and ‘00s found clear focal points for their activities. LA County Metro was in the process of building its Red Line subway, connecting the San Fernando Valley to Downtown LA, which included three stations in Hollywood. The Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) of Los Angeles promoted growth near those stations, located along Hollywood Boulevard at Highland Avenue, Vine Street, and Western Avenue, through lot assemblage and tax increment financing plans. According to former CRA historian Donald Spivack, the agency concentrated its initial actions near the easternmost station at Hollywood/Western, which was located in the most economically deprived of the three areas. They supported the efforts of firms such as McCormack Baron Salazar, an affordable housing developer, to build the Metro Hollywood apartment building, which opened in 2003 as one of the earlier transit-oriented development projects in LA.

Alongside its work in the vicinity of the Hollywood/Western station, the CRA focused attention on the Hollywood/Highland station at the western edge of Hollywood. The sense the CRA had was that the Hollywood/Highland station area needed only a small push to become a bustling and prosperous area. It was already frequented by a steady stream of tourists, and was closest to the wealthier neighborhoods to the west of Hollywood. The Hollywood and Highland Center, developed by TrizecHahn in 2001, added a substantial amount of retail and a large hotel to this area, which was previously characterized more by low-end souvenir shops. This project also added the 637-room Loew’s Hotel to Hollywood. Some people quibble with the aesthetics and site layout of the Hollywood and Highland Center, but there is no doubt that its area contains substantially more commercial activity today than it did before the center was built. The CRA also supported the renovation of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel near the Highland Avenue station, performed by Gaw Capital Partners in 1995, and the W Hotel near the Vine Street station, developed by Starwood in 2010. With these projects, the Hollywood Boulevard area was firmly reestablished as a tourist destination.

Hollywood began to add to its housing supply around this time, as well. LA’s Adaptive Reuse Ordinance of 1999 allowed developers to convert underutilized commercial properties into apartments and condominiums. The bulk of that sort of activity took place in Downtown LA, but a fair amount was pursued in Hollywood as well, adding residences that attracted creative professionals to the neighborhood.

But perhaps more important than the addition of these creative residents to Hollywood in this time was the introduction of the sorts of businesses at which they would work. Media companies, including early movers such as Nielsen and CNN, began to repopulate Hollywood in the 1990s. They were attracted by its lower rents, by its convenience to other industry nodes in the West Side and East Valley, and by generous parking and other incentives provided by the CRA. Moreover, many entertainment firms decamped from Hollywood when they came to need more space for production than could be found in an urban environment. As the movie business grew ever more digital around the turn of the 21st century, the need for spacious backlots was reduced in favor of office desk space for computer-based work.

Hollywood Today

The Hollywood of tomorrow is still emerging, but we can begin to observe its basic contours. Like much of LA, its hubs of activity are centered on distinctive commercial boulevards. In Hollywood, its three main corridors, Hollywood Boulevard, Sunset Boulevard, and Santa Monica Boulevard are each developing individual identities, such that over the years to come we may come to recognize a few districts within the Hollywood neighborhood. The Hollywood Walk of Fame District is centered on Hollywood Boulevard, the Hollywood Vinyl District is centered on Sunset Boulevard, and the Hollywood Media District is centered on Santa Monica Boulevard.

Until quite recently, for most people “Hollywood” referred to the area along Hollywood Boulevard and a few surrounding streets. It served primarily as a tourist destination for visitors seeking to commune with its star-studded history, as represented by the famous stars in the sidewalk on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce installed these stars in the streets in the 1950s, precisely during the time when the industry was vacating the neighborhood! Today, Hollywood Boulevard remains primarily a tourist destination. But retail, hotel, and entertainment additions made over the past 20 years have made its offerings much more robust.

The more transformative changes have been made to the south of Hollywood Boulevard, along Sunset Boulevard, Selma Avenue, and their cross-streets. These streets have seen the bulk of new development in Hollywood thus far, including several high rise office, hotel, and residential projects. Collectively, the projects emerging along these corridors are charting the course for Hollywood’s economic and cultural future, sending it a different direction from those which have characterized the neighborhood over years past. Surely the most important economic addition to the neighborhood is the addition of Netflix studio offices at Icon and EPIC, completed by Hudson Pacific Properties in 2016 and 2020 respectively, as well as at Kilroy Realty’s Academy on Vine in 2020. Netflix has been so prolific in content production, spending an expected $15 billion this year, that it is affecting the industry’s center of gravity, pulling contractor and other studio offices closer to Hollywood.

Another new mixed-use project on Sunset Boulevard, the Columbia Square renovation project by Kilroy Realty Group, features elevated restaurants, the co-working space / members club NeueHouse, the Rooftop Cinema Club experience, and a luxury apartment tower where rents begin at $3,580 for a 1-bedroom. One suspects that such outlets would be hard-pressed to operate on Hollywood Boulevard immediately to the north, viewing it as being too mass-market and touristy. But just a couple of blocks away, the tenor of the neighborhood is substantially different, such that we can begin to think of this area as having its own identity.

This newfound identity is punctuated by a raft of new hotel developments emerging in the area along Selma Avenue, most of them developed by a firm called Relevant Group. Beginning their efforts in the neighborhood in the ‘00s, the Relevant Group recognized a growing demand for Hollywood hotel space as the local economic base grew. At the time, the only major full service hotels in Hollywood were the Loew’s Hotel, the Hollywood Roosevelt, and the W Hollywood. In a fashion similar to the development of many properties in DTLA, the projects developed by Relevant Group in Hollywood were funded largely by Chinese capital seeking a safe haven in the United States, and EB-5 investor visas for individuals to establish legal residency here.

The first major project Relevant Group has completed in Hollywood is the Dream Hotel. This hotel rapidly emerged as a food and beverage destination, including NYC-import restaurants such as Tao and Beauty & Essex, as well as a popular rooftop pool and bar. The lineup of hotels currently in the firm’s portfolio under construction reveals the breadth of target audiences to which the new Hollywood is seeking to appeal. The Thompson Hotel aims for lifestyle travelers. The Tommie Hotel targets millennials looking for affordable, if compact, rooms in a stylish and well located space. A yet-to-be-branded hotel will offer larger format suites for celebrities and executives in LA for a slightly longer stay. The old Citizen News Building in the area is being converted into conference and event space.

The final major area of Hollywood in the midst of a transformation is the Hollywood Media District. Generally oriented around Santa Monica Boulevard in the vicinity of Highland Avenue and La Brea Avenue, the Hollywood Media District is distinctive from almost every other neighborhood in its part of the city given its industrial heritage. This neighborhood was traditionally where industrial processes needed for filmmaking took place, in the day when special effects were produced by chemicals rather than computers. As the entertainment industry shifted toward digital production in the late 20th century, that economic impetus for the Hollywood Media District began to wane. But a legacy of industrial buildings and zoning in the neighborhood remain.

The thrust of the modern development boom in the Hollywood Media District began in earnest as the economy began to recover from the Great Recession about 10 years ago. Given the industrial zoning and nature of the Hollywood Media District, much of the new development there has been office, as residential use is typically not permitted in industrial zones in LA. Over the past 10 years, the content production industry has boomed along with the growth in demand for it over the internet.

Office development in the Hollywood Media District has largely served that use. Producers of this sort of content often prefer the more spacious floorplates allowed by the formerly industrial buildings to be found in the Hollywood Media District, and the relatively availability of land in this neighborhood allows for more ambitious development projects. CIM Group, one of the more prolific developers in this neighborhood, has adopted a strategy of preserving and repurposing as many low-density, formerly industrial structures in this neighborhood as possible, while transferring their density rights to adjacent new office buildings. This type of approach may allow the Hollywood Media District to maintain its historic character, while adapting to a new wave of use.

The Hollywood Media District today is practically one giant construction site, but as its projects near completion, the contours of its emerging culture are forming. As is the case with many formerly industrial neighborhoods around the world, art galleries have been some of the first movers into the Hollywood Media District. The Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, run by the former curator of MOCA, and the galleries located in the art deco former Howard Hughes office building at 7000 Romaine Street, are particularly notable. Landmark retail outlets such as Sightglass Coffee and Tartine are opening in the neighborhood.

Large scale residential projects, such as the 695-unit AVA Hollywood projects, are sure to add more round-the-clock vitality to the area. The Hollywood Media District is described by its promoters as a “hole in the donut” between existing vibrant neighborhoods: West Hollywood, Central Hollywood, Hancock Park, and Fairfax. Ultimately, and more specifically, it could grow into a more westerly version of DTLA’s Arts District, a hub of industrial cool and employment with a diverse set of surroundings.

Hollywood Tomorrow

As we look toward the Hollywood of tomorrow, what we see is the emergence of a few distinct neighborhoods, where in the past Hollywood had been thought of more as an undifferentiated whole. The Hollywood Walk of Fame, the Hollywood Vinyl District, and the Hollywood Media District all have their own unique characters, and may evolve in different directions over the years to come.

Notably, however, promoters for both the Hollywood Vinyl District and the Hollywood Media District compare both neighborhoods specifically to the Meatpacking District in New York City. There is some sense to this analogy. All three areas were somewhat peripheral over decades past, yet have grown as lifestyle and employment centers over recent years. They can also make use of historic industrial buildings, combining old with new in design. And they all can capitalize upon a significant tourist presence, via the allure of Hollywood and via that of the High Line park in New York.

There will be three main forces guiding the future direction of growth in Hollywood. The first is the new Hollywood Community Plan Update. The current Hollywood Community Plan, in place since 1988, is relatively anti-growth as compared to the plan proposed to replace it. This existing Community Plan actually was replaced with a new one in 2012, however a 2014 court decision rescinded the 2012 Plan, so the 1988 Plan was put back into effect. The City is in the process of finalizing its new Hollywood Community Plan, which it anticipates putting into effect in 2020. The new development allowed through this plan will further the urban character of Central Hollywood.

The second major force guiding development in Hollywood over years to come is the precise alignment of the Metro Crenshaw Line northern extension. The Metro Crenshaw/LAX Line is set to open next year in 2020 between LAX and the Expo/Crenshaw station. Metro has plans to expand service northward, ultimately linking this line to the Hollywood/Highland Station. Its chosen alignment may be along San Vicente Boulevard via West Hollywood. It may be along Fairfax Avenue or La Brea Avenue through their respective districts. Whichever alignment is chosen, the commercial and cultural links formed via the new transit connection will have an impact on the sort of development promoted in Hollywood over decades to come.

Finally, future growth in Hollywood will be heavily influenced by the debate surrounding densification and congestion, housing and gentrification, a discussion that is endemic throughout Los Angeles. Hollywood has two key constituencies that are likely to make development in the neighborhood more contentious than it is in other more urbanized area such as DTLA. Unlike DTLA, the residential population in Hollywood never entirely hollowed out. Many people, predominantly lower income, have lived in Hollywood for decades before the recent development boom, and will continue to voice their concerns over potential displacement. Hollywood also has a higher-income population that mostly lives in its hillside areas and is therefore inherently auto-dependent. The expansion of public transportation in central Hollywood does not eliminate their need for parking or susceptibility to automobile traffic. These hillside homeowners will likely continue to voice their concerns over decades to come as well.

Hollywood has long been the world’s center of storytelling. The heady tale of Hollywood and Hollywood – split from each decades ago – arrives at its stirring reunion scene, with all of the rediscovery and realignment which this entails.

Jason Lopata is a Master of Real Estate Development (MRED) student at USC. Previously, he worked as a land use consultant with Craig Lawson & Co., LLC, helping real estate development projects in LA navigate the city approvals process, and he spent time on the Business Team of LA Mayor Eric Garcetti. He also writes articles on globalization and urban development for Stratfor, the geopolitical analysis website. Jason received his bachelor’s degree from Stanford University and completed programs of study at the University of Oxford and at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. While at Stanford, he founded and led the student real estate organization, and authored his senior thesis on Los Angeles development over the past 30 years.