Los Angeles has found itself in an identity crisis, with many of its low-slung neighborhoods now in direct conflict with the harsh realities of a housing shortage.

Some have sought to combat the region's rental crunch by increasing housing supply through high-density developments. Mayor Eric Garcetti, as well as several other state and local officials, have looked to ease the construction process through a variety of measures such as streamlining permitting and speeding environmental lawsuits against large projects.

Opponents have countered by asserting that many of these developments threaten renters and homeowners alike, and have placed a citizen's initiative on the March 2017 ballot designed to limit their construction. One of their main points of contention is "spot zoning," or the practice of rezoning properties to allow for higher densities than originally permitted by the city's patchwork of community plans.

With spot zoning now under harsh scrutiny, new research published by the UCLA Anderson Forescast and the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate takes a closer look at when and where this practice actually occurs.

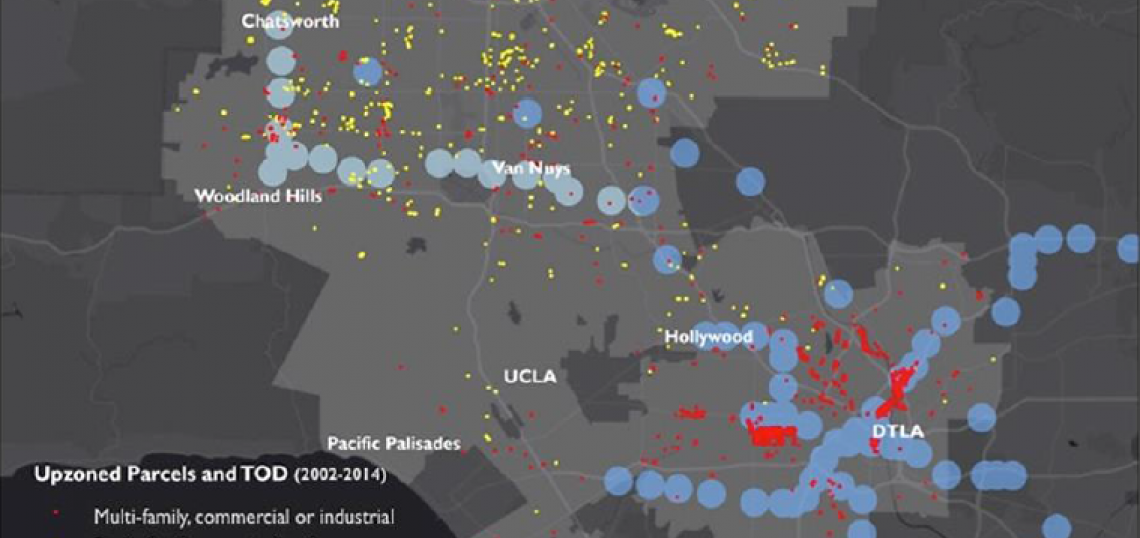

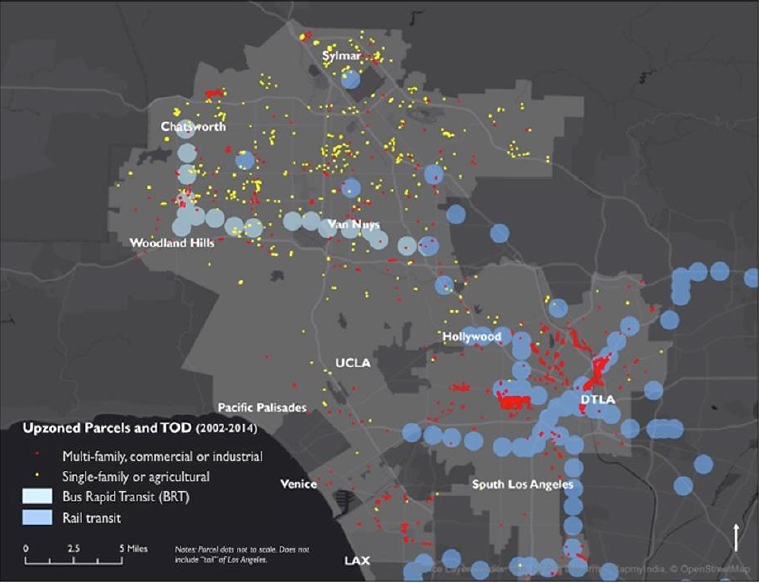

The report, authored by urban planner C.J. Gabbe, tracked the zoning of every parcel in Los Angeles between 2002 and 2014. Properties which allowed for more residential density at the end of the 12-year period were determined to be "upzoned," while those which could accommodate less density were regarded as "downzoned."

The results, as it turns out, confirmed much conventional wisdom about neighborhood-level politics in Los Angeles. Gabbe wrote the following:

"Zoning designations were largely static: On average, the City upzoned 225 acres and downzoned 216 acres annually between 2002 and 2014. (Los Angeles' total land area is about 300,000 acres.) That is less than two-tenths of one percent of its land area every year. And, many of these changes, particularly the downzonings, were more administrative than substantial changes to the City's residential development capacity."

These findings led Gabbe to note that upzoning occurs on an infrequent basis, which runs counter to the assertions of many critics of the practice. In comparison, a similar analysis from New York University found that New York City rezoned approximately 20% of its total land area during the six-year period between 2003 and 2009, including 5% for upzoning and 6% for downzoning.

For Los Angeles, the report found that upzoning "follows the path of least political resistance and most development potential." Specifically, parcels that were previously zoned for low-intensity uses such as parking or manufacturing were 85% more likely to be upzoned. Additionally, most upzoned parcels were located within close proximity to freeways. In fact, for every additional mile a parcel was located away from a freeway ramp, the odds of upzoning were cut in half.

Neighborhoods with high homeownership rates were found to be much less likely to see increased residential density. Gabbe's analysis found that parcels in neighborhoods within the City's top quartile for homeownership rate were 96% less likely to be upzoned than those in the bottom quartile.

Proximity to amenities such as the beach and high-quality schools also had a negative impact on the potential for upzoning. For each mile away from the beach, a parcel was found to be 56% more likely to be upzoned. For every 100-point increase in an elementary school's Academic Performance Index, the odds of upzoning in the surrounding neighborhood decreased by 15%.

When overlayed on a map, instances of upzoning for multifamily residential development are concentrated within Central Los Angeles, particularly in Downtown and Mid-Wilshire. Many zone changes were initiated by individual property owners, such as those seen in the San Fernando Valley. Broader changes resulted through the implementation of new community and specific plans, such as the Cornfield Arroyo Seco Specific Plan in Chinatown. Very little upzoning occurred on the Westside, outside of an isolated patch in Playa Vista.

Gabbe concludes that in Los Angeles, like in other major cities across the country, the most desirable neighborhoods with access to valuable amenities are also the most difficult to upzone.

- Where Residential Density Is Allowed - and Isn't - in Los Angeles (UCLA Anderson Forecast)